Invisible Innovator : Bringing Russell and Jones to USF, He Showed Basketball Fans Future of the Game in 1950s

Even among college basketball aficionados, Phil Woolpert is hardly a household name.

It isn’t because of his record. In 1955, at 39, he coached the University of San Francisco to an NCAA championship. A year later, he won it again, only one of nine coaches ever to repeat. And his 60-game winning streak at USF is still the second longest of any Division I school.

Yet, even when he was posthumously enshrined into the Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield, Mass., earlier this month, a clear picture of Woolpert did not emerge. In the short video shown about him at the induction ceremony, most of the images were actually of his two greatest players, K.C. Jones and Bill Russell.

“Phil Woolpert is still the invisible great coach,” Jones remarked a few years ago.

Woolpert’s most lasting contribution to college basketball, however, was not his impressive string of victories in the 1950s. Instead, during an era when not many white coaches were accepting black players, Woolpert stormed across the color line and presented the nation with its first truly visible, integrated college basketball team.

Born in Kentucky in 1916, but raised in Los Angeles, Phil Woolpert was the athletically inclined member of a family of free-thinking political activists. Tall and thin, he graduated from Manual Arts High School, then attended Los Angeles Junior College, where he played basketball.

In 1936, he transferred to Loyola--now Loyola Marymount--where he played varsity basketball with another future coaching legend, Pete Newell.

College basketball in Southern California during the late 1930s was a far cry from today’s game. Scores were low, crowds were small and gyms were hard to come by. During Woolpert’s first year at Loyola, the Lions practiced in a ballroom at the end of the old Santa Monica Pier.

“You could hear the water rushing underneath,” Woolpert told a reporter years later. “(And) the building would shake

when the big waves would hit.”

After graduating from Loyola in 1940, Woolpert took a job as a counselor at the California State Prison Farm in Chino. During World War II he served in the Army, which, to his surprise, actually made him into a prison guard. Unfortunately, however, he was assigned to Schofield Barracks in Hawaii, where he served under the brutal, sadistic officer who was later fictionalized in James Jones’ novel, “From Here to Eternity.” The conditions at Schofield disturbed him deeply.

“He never really got over that,” Newell said.

Returning to the States after the war, he married Mary Golden, who shared his passion for basketball. And in 1946, he got a chance to coach.

Newell had become the basketball coach at the University of San Francisco, and he helped Woolpert get hired next door, at St. Ignatius High. Two years later, Woolpert joined Newell at USF, coaching the freshman team and serving as his old friend’s assistant coach.

It was an extremely productive period for the two men, who fashioned an innovative and defensive-oriented approach to the game. In 1949, the Dons won the National Invitation Tournament, becoming the unofficial national champions. A year later, Newell left for Michigan State, leaving Woolpert as his heir-apparent at USF.

But there was a hitch. During the Great Depression, Woolpert’s parents were widely known in California as proponents of the Townsend Old-Age Pension plan, a radical social security proposal. As much as the administration at USF liked Phil, they were worried, in those days of McCarthyism, about his political views.

“Only when I told them that Phil wasn’t a communist would they hire him,” Newell recalled.

Woolpert’s early years were hardly auspicious. His teams went 44-48 in his first four seasons, and there was grumbling among the alumni about whether he would have much of a future.

As it turned out, he was helping to rewrite the future.

At the dawn of the 1950s, college basketball--like most aspects of American life--was a segregated affair. Except at all-black schools, African-American players were neither sought out nor welcome at most colleges and universities.

But Woolpert saw things differently. Having played on an integrated team at Los Angeles Junior College, and worked with blacks at Chino, he was sensitive to the plight of minorities in America, particularly after some family friends of Japanese descent were interned during the war. At USF, Woolpert didn’t simply open the door to black basketball players but, unlike the coaches at some other West Coast schools, he did not limit the number of blacks on his team. And because of that, he acquired two of the decade’s greatest college players.

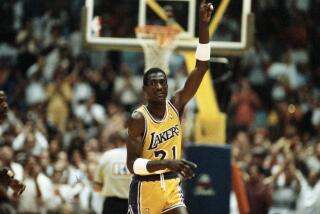

In 1951, Woolpert offered a scholarship to K.C. Jones, a talented football and basketball player who had planned, after graduating from San Francisco’s Commerce High, to go to work for the post office. A year later, Woolpert took on a gangly Oakland bookworm by he name of Bill Russell who, like Jones, had not been recruited by any other schools. Other black players followed.

They changed more than just the complexion of the game. They also brought with them a looser, more inventive style of play, one that had been developing on the playgrounds of black America. In time, it would revolutionize basketball.

Woolpert liked what he saw and allowed his players to incorporate elements of playground style into USF’s game. But he also made his own contributions. He grounded his players in fundamentals, honed their defensive skills and employed a complex strategy of “reverse action” on offense. He was also highly competitive--and not just at basketball.

“He used to keep us kids up way past our bedtimes, sometimes past midnight,” his son, Phil, remembered, “just so he could win the last game of Yahtzee.”

The combination proved powerful. In 1955, Jones and Russell led the Dons to the national championship. The next season, they went undefeated and won the NCAA tournament for a second time. The ever-skinny Woolpert, dubbed “the Thin Man” by reporters, and the Dons had become the nation’s basketball powerhouse.

But they also ruffled some feathers. Woolpert not only started three black players, but played even more.

“Phil was his own person, playing five black players when advised otherwise,” Jones wrote recently.

While many other white coaches dallied with integration, Woolpert and the Dons kicked down the door.

And they paid for it. The Dons were regularly subjected to racist taunts--and worse--at games. At the All-College Festival in Oklahoma City in December, 1954, angry fans threw pennies and seat cushions at them.

But their game against Loyola of New Orleans a year later was their greatest test. Only three days earlier, the Bradley Braves had gone to New Orleans to face Loyola at Tulane Auditorium. Bradley had a black player on its team, but the coach, fearing for his player’s safety at the hands of the all-white crowd, kept him off the floor.

The same crowd was back for the USF-Loyola game. But Woolpert and his players refused to be intimidated, and played in what was one of the earliest integrated college basketball games in the Deep South.

It was not without incident. Objects and taunts were thrown, and when Russell fouled out, the student announcer hummed “Bye, Bye, Blackbird” into his microphone. The Dons beat Loyola, 61-43, and escaped the auditorium unhurt, but there was one final indignity. None of the downtown hotels would accept the black players, so the national champions had to spend the night in different parts of town.

The next season, 1956-57, Woolpert fielded another able team, but with Russell and Jones gone, it could not maintain the unbeaten streak. The team did make it to the 1957 NCAA championship tournament, though, where it was beaten by Wilt Chamberlain’s Kansas squad in the semifinals.

A year later, Woolpert led another strong team into the NCAA tournament but the Dons lost to Elgin Baylor’s Seattle University team. The desegregation of college basketball that USF had helped create was well under way.

Yet even with his success, the pressures of coaching had affected Woolpert’s health. In 1959, under orders from his physician, he resigned from USF. He tried his hand at business, but ultimately found the call of the hardwood to be too strong. In 1961, he briefly coached the San Francisco Saints of the American Basketball League.

A year later, he was appointed coach at the University of San Diego and coached the Toreros for seven years, but never approached his earlier success. In 1969, citing a “declining interest in the game,” he resigned as coach, but kept his job as athletic director.

Four years later, he left college athletics forever. He and Mary moved to a rustic home outside of Seguim, Wash., on the Olympic peninsula, where he drove the local school bus.

“He had grown totally disgusted with organized society,” said Bernie Bickerstaff, general manager of the Denver Nuggets, who played under Woolpert and served as his assistant at San Diego.

His last years were spent very much out of the spotlight. But before he died in 1987, Woolpert reappeared at least once, briefly, on the scene of earlier triumphs.

In February, 1973, four weeks after John Wooden’s UCLA team surpassed USF’s 60-game winning streak, Phil and Mary attended a game at USF, sitting up in the stands at Memorial Auditorium. But only a few people recognized them. Most of the crowd had no idea who the thin, elderly man was, and what he had to do with college basketball. They didn’t know about “the invisible great coach.”

Scott Ellsworth, a historian at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, is writing a book about the 1957 Final Four.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.