Bataan March Survivor Found a True Friend Among Enemy

For Morgan Jones, April 9 brings a blur of bittersweet memories. It isn’t just the beginning of spring, or the opening of baseball season, or a better time to drive a ball down the fairway.

It’s a time to remember how lucky he is to be alive--and how the sergeant who once held him captive in a squalid Japanese prison ended up being his friend for life.

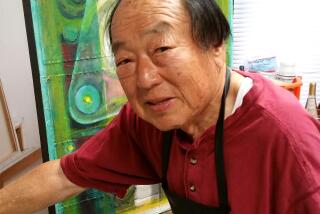

Jones, 75, a retired railroad freight engineer who lives at Lake San Marcos for the lure of golf, survived the Bataan Death March, one of the most infamous episodes of World War II.

It was half a century ago today--April 9, 1942--that American defenders surrendered to the Japanese on the Bataan peninsula in the Philippines, on the island of Luzon.

Jones, as a reluctant member of the New Mexico National Guard, was one of 37,000 U.S. and Filipino soldiers captured at Bataan, near the volcanic Zambales Mountains.

Thousands died during the 70-mile “Death March” from Mariveles, at the tip of the peninsula, to a concentration camp at San Fernando.

Jones was spared having to walk the whole distance--his regiment was transported part of the way by truck--but he remembers being deprived of water and later, during his internment, being beaten to a pulp.

“You can go without food, but going without water turns a person into an animal,” he said. “Sometimes, it all comes back to me in flashbacks . . . the strain of being a prisoner and not understanding what they were shouting about, and hitting you when you didn’t know why, or what they were talking about. . . . One of the beatings came close to my eyes. That was the worst.”

Recalling such terrible moments even now brings a shortness of breath. For seconds, Jones must stop. To free himself and move on, he talks about golf, or his children, or he steers the memory to more benign recollections.

Bataan was retaken by U.S. forces under Gen. Douglas MacArthur in February, 1945, but, by that time, Jones was long gone. In 1944, he and thousands of other prisoners were put on a ship headed for Taiwan. He remembers with nightmarish clarity the six weeks spent huddled among hordes of sweating, starving prisoners in the darkened hull of a ship.

“Taiwan was 500 miles away,” he said, again finding it difficult to breathe. “We were sitting on coal, crowded together so closely we could hardly sit down.

“There was very little air, very little food, very little water . . . That was even worse than the death march. Six weeks in the hull of a ship, when you couldn’t see anything, and you’re being bombed and strafed--by American planes whose pilots didn’t know we were there.”

Jones, who grew up in dusty, rural Clovis, N.M., not far from Lubbock, Tex., where he attended Texas Tech University, felt so far from home--from family and friends.

He spent three months in Taiwan, where, on his last day, getting ready to be shipped out again, he and his fellow prisoners endured another round of American air attacks.

“They sank one POW ship, but none were marked,” Jones said sadly. “They didn’t even know they were killing their own people.”

Jones ended up in the cold copper mining town of Kosaka, Japan, where one of his worst memories was having to contend with 8 feet of snow.

As the oldest ranking American prisoner, a near-30 staff sergeant, Jones, who describes himself as “the worst cook you can imagine,” was made the camp’s mess sergeant. It was during this period, from January to September, 1945, that Jones befriended his guard, Sgt. Masakichi Ogata, whom he knew as Ogata-san.

They spoke in Japanese, a language Jones learned during his captivity.

“We spent many a night behind the fires in the kitchen talking about our lives,” Jones said. “He was just like me--he didn’t want to go to war but got caught in it. I only joined the New Mexico National Guard to avoid being drafted.

“By that time, Ogata-san had served enough time and didn’t have to fight any more. And what we found out was, we weren’t too different. We had hopes and dreams and loved ones, and just wanted to live.”

Jones’ daughter-in-law, Orange County attorney Ronna Reed, 36, is touched by this improbable friendship.

“It happened near the end of the war, when the Japanese were making a transition from being aggressors and victors to being on the losing side,” Reed said. “His experience was just horrible in the beginning--the nightmares, the beatings. . . . It was a miracle he survived.

“But the prison camp in Japan, where he met Ogata-san, was probably the least traumatic of all the camps he stayed in,” she said. “The food rations were so scarce, it was close to starvation, but it was survivable.

“And there was an opportunity there, just the two of them sitting in the kitchen day after day, talking, realizing they had little in common, but learning--I think--that they were both remarkable and good people, with a lot of love in their hearts.”

Long after the end of the war, Jones decided to look for Ogata-san, with whom he had lost touch. It was 1972, and Jones’ son--Reed’s husband--had received a fellowship from Stanford University to study Chinese in Taiwan.

So, Jones and his wife planned a trip to the Orient, which included a visit to Japan. Jones pulled out a notebook, which contained Ogata-san’s address. He wrote but received no reply. In the letter, however, he told him the name of the hotel in Tokyo where he and his wife were booked.

Upon arrival, Jones heard from the desk clerk that Ogata-san had been looking for him--desperately--and urged him to call right away. They spoke by phone; the friendship was officially renewed.

For both, though, the reunion was unsatisfying. Ogata-san was unable to meet his friend in person, and, for five years, daughter-in-law Reed said, the former prison guard wrote to his American inmate and plotted ways they could somehow meet again.

The true reunion happened in 1978. Jones and his wife, whom he met and married after the war, went to Ogata-san’s hometown, Yonazewa, to spend 10 days with him and his family. Ogata-san even took him to Kosaka, where he was reunited with two other captors, who seemed thrilled to see him.

Jones remembers being short of money on the trip, and his former guard loaned him enough to pay his hotel bill and tide him over for the rest of the trip. Jones remembers two men, different in language, culture and custom, reminiscing about how much they liked each other, and how similar their lives had been, despite being worlds apart.

Ogata-san died the next year, in 1979. Jones has kept in close contact with Ogata-san’s family. But he marvels at the fact that, in 1978, the last time he saw Ogata-san, his friend was dying of cancer, “and didn’t even tell me.”

Looking back at the war, Jones said he has “no animosity toward Japanese . . . even with all the bashing they’ve been giving us lately. My experience was extraordinarily rewarding and beneficial--but only if you survived. I do not want to repeat it or have anyone else endure it.

“It was quite educational, worth a million dollars, and I would not pay anything to do it again. As far as treatment, they treated us horrible at times and treated us wonderful at times. But Ogata-san was always very nice to me.”

Jones said he is often jarred awake by flashbacks, cold sweats, incomprehensible nightmares in the middle of the night. The shortage of breath, the symptom he incurred as a lasting reminder of the horror, prompted him years ago to seek out a psychiatrist.

“But, at $50 for half an hour, well,” Jones said, “I got better pretty quick.”

His daughter-in-law said that, until just a few years ago, Jones had avoided talking about the war as much as possible. And the only thing he wants to remember today, he said, on the golden anniversary of a not-so-golden time, is the friendship he formed with Ogata-san.

“His wife told us on our visit in ’78 that that was the happiest time of his life,” Jones said of Ogata-san. “I want him to know, I feel the same about him. War is war, but friends are friends, and I’ll never forget knowing him.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.