Playing With Fire : It Was a Long, Hot Job for ‘Backdraft’ Effects Team

LOS ANGELES — Critics may be divided about the merits of Ron Howard’s “Backdraft,” a new film about firefighters, but they’re pretty much unanimous in praising the film’s sizzling special effects.

The movie stars William Baldwin, Kurt Russell, Robert De Niro and Scott Glenn as Chicago firefighters, but the fire itself becomes a mysterious, lifelike character that hovers and threatens. The film’s title refers to a firefighters term for the way a smoking fire, that appears to be retreating, explodes when it receives oxygen.

Eight months of creating fire effects so consumed designer Allen Hall and first-unit supervisor Clay Pinney that for long after the filming neither could bear to look at a blaze, let alone talk about one. What made matters worse was that the two had begun “Backdraft” almost immediately after completing work on the huge warehouse fire that caps Barry Levinson’s “Avalon.”

“On the first day we were in Chicago for ‘Backdraft,’ there was fire. And on the last day there was fire,” Hall said in an interview recently at Hollywood’s Special Effects Unlimited Inc., a company that supplied many of the materials for “Backdraft’s” fires.

“I was telling Clay last night when we saw the finished film that it was really nice to know there was dialogue in the movie,” he joked.

“It’s the real thing up on the screen,” Hall said. “Anyone who was on that set who got minor burns will tell you so. Especially the ones who were given what we began to call ‘the haircut on the set’--when the hair on their foreheads was singed.”

During the five months of filming, Hall and Pinney recalled, the actors and crew were often at risk but no one was seriously injured by fire. They said Universal Pictures was concerned about the potential liability and was hesitant to commit to the project. But both said the promise of strong safety precautions--such as having members of the Chicago Fire Department on the set at all times--helped allay the studio’s fears.

Co-executive producer Brian Grazer said that in the end the insurance cost was based on the movie’s $35-million production budget and wasn’t affected by the risks involved.

One of the most dangerous assignments went to cinematographer Mikael Solomon, who performed his job wearing special gels and fire-retardant clothing of the kind used by racing car drivers. He usually hand-carried a shielded camera through roaring fires.

“We only burned his eyebrows off once,” said Pinney with a laugh.

Neither Pinney nor Hall could recall a time when he had worked as heavily in an action-oriented movie with the principal stars (all of the leading actors of “Backdraft” went out on actual calls with the Chicago Fire Department in preparing for their roles).

“It was Kurt Russell, in my opinion, who really pulled those guys together and was the one who was out front, charging into the stuff all the time,” Pinney said.

“It became kind of a competition too, kind of a macho thing,” said Hall. “Kurt would say, ‘Billy Baldwin just got to run through a fire. Can you guys set something up so I can run through a fire too?’ ”

In the climactic scene, an enormous chemical warehouse fire, actors Baldwin, Russell and Glenn are 30 feet above a raging blaze. For protection, they were cabled together so they could not fall.

Glenn, who was closest to the flames, wore protective clothing and skin gels. “We were underneath shooting the flames (at him), and it was hot,” Pinney said. “You wonder how they could handle it. At one point the flames burned Glenn on the inner leg, when a pant leg split open.”

The power of the blaze created for the chemical warehouse surprised even Hall and Pinney, they said. “When we first showed Ron (Howard) the test of the fire, we blew out three stories of windows,” Hall said. “Things got so heated that chunks of concrete were falling out. We actually caused structural damage. The Chicago firemen spent many hours putting that one out.”

“Backdraft’s” fire effects required a budget of $1.25 million, Hall said, and took four teams to create--from researching the materials to lighting and controlling the fires on the set. Both praised the Chicago Fire Department, which in addition to helping in safety matters gave advice on realism.

Most of the fire effects were shaped each day on the set, Hall said. “We’d have all of this wild equipment ready, and we’d dress the camera (with fireproofing). And we’d always have 12 to 14 guys and more sometimes. The shooting was continually supported by propane mortars that would shoot fireballs.

“One of the things that the real firefighters had said they hated most about Hollywood pictures about fire, including ‘The Towering Inferno,’ is that they are totally unrealistic when they don’t show the ash and the smoke that are ever-present inside fires,” Hall said.

Firefighters from across Los Angeles County were impressed with the film, which many saw last week in special screenings arranged by Howard.

Battalion Chief John Badgett of the Los Angeles City Fire Department said the consensus among the firefighters he spoke with was that “the special effects were incredible . . . the flame footage was as close to real fire as I’ve ever seen.”

Badgett’s only major criticism about the film’s veracity concerned how some of the firefighters are portrayed as rushing into fires without breathing devices. “We don’t take unnecessary risks,” he said. “I think the firefighters in the movie were scripted to be more overzealous than what we would be.”

And, Badgett said, “A real fire has lots of smoke and they weren’t able to show that.” But he said the fire professionals understand the problem. “In a movie it’s either no smoke or not seeing the actors.”

Hall and Pinney realized the problem of shooting with smoke early on. So they substituted a white, haze-like effect that gives the impression of smoke without blocking the camera’s view. Producing the the impression of flying ash, however, was another matter. The drive for realism led to the creation of a device they call the “ash-o-matic.”

“We burned a special cardboard that makes a very nice ash that floats through the air,” Pinney said. “Then we found some air movers that are used in mining to clear the air, and we combined them so that the ashes floated through the air and down all over the set.

“It was something the actors ended up hating,” he said, “because these little burning embers would come down and land on their neck and on their face . . . it was irritating.”

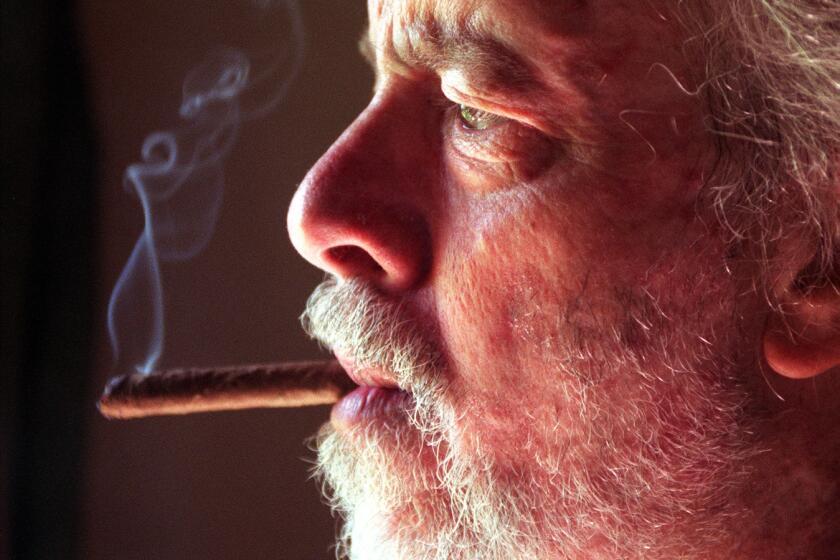

Some of the movie’s more eye-catching scenes are those when fire appears to come to life. In the movie, De Niro’s character calls it “the beast” or “the animal.”

To achieve these effects and to make the “beast” travel, Hall and Pinney applied an elemental rule: Fire is lighter than air and, like an air bubble in water, travels upward.

“We had one room where we let some flammable fluid loose--it was slightly on an angle and fluid would roll down, igniting as it went.”

Another room was built upside down and was filmed in a way much like the famous scene in “Royal Wedding” in which Fred Astaire dances from floor to wall to ceiling. Said Pinney: “The liquid would travel across the screen, then the fire would go down the walls. But when you look at it (on film), it’s running across the ceiling, then the fire shoots down the walls.”

What was most bizarre to both men was the phenomenon that they could create a raging fire and then when the director yelled “Cut!” they could turn off the blaze in an instant.

As one fire blurred into the next fire, the cast and crew tended to grow casual. “But it was at that point when we had to be twice as careful,” Pinney said.

“Initially, if we started a fire up, people would back off from it. But by the end of the show, if it was a chilly morning, you’d pilot up the fires and people would be standing nearby, like it was a fireplace, warming their hands.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.