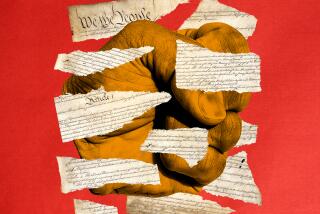

COLUMN ONE : Bulgaria’s Ideology Gridlock : Torn between Communists and the opposition, citizens aren’t sure they want change or even need it. They fear the disorder of democracy.

KOPRIVSHTITSA, Bulgaria — Fallen leaves lay wetly at the roadside and smelled of autumn. In the market, peddlers buttoned their collars tighter and sold soft, sweet pears, the last of summer’s produce. Along Koprivshtitsa’s cobbled streets, the whine of an electric saw rang out at a steady rhythm as three men fed logs to the blade and cut wood for winter fireplaces.

Amid the long shadows of the late afternoon passed a farmer, 60 years old, sturdy as an oak stump, just in from his fields two miles outside town. He had walked this distance with his wife and a neighbor, leading a bay pony that strained in its traces to pull a wooden wagon heaped with sacks of freshly dug potatoes.

This is a mountain village where time and season are read by the light in the sky, and matters are judged by hard evidence and old measures. The farmer, applying the strict local standards of his occupation, is inclined toward the the values of “hard work and good sense” in the guidance of his life. At the moment, good sense comes down to this:

“My potatoes are going into my storeroom, in my house, not to anywhere else. Not to town, not to the market, not to Sofia (the capital). I will put them in my larder, and I will eat them.”

And that is the emphatic countryside verdict on the dislocation and dysfunction of political reform in Bulgaria, a country whose city dwellers and freshly named government wonder where all the food is going and, even more worrying, where it might be three months from now, in the face of winter’s full force.

This is Balkan Bulgaria, a country suspended between the Communists and the anti-Communists of a new age, and uncertain which way it wants to go. It is not sure if it wants or needs economic changes, and it is less than confident about the rambunctious disorder that accompanies democracy.

Bulgaria is a gentle, sweet-tempered country, the geographical divide between Eastern Europe and the cusp of Asia, where the music sounds Middle Eastern, the written script is Cyrillic, the bloodlines Slavic or dark-eyed Turk or a mix of both. It is that rare former Soviet satellite country where the Russians remain popular, and where a largely peasant culture has always been comfortable enough with the idea of a maximum leader guiding its destiny from the top.

The farmer in Koprivshtitsa is far from rare. He voted for the victorious Communists, now calling themselves Socialists, in the June elections not because he favors totalitarian government but because, for all his adult life, he has lived with it, made peace with it, worked out its system of favors granted for favors returned. Most important, at least to him, it was orderly.

And he is in no mood to feed further disruption with his own underpriced potatoes.

“Let the lunatics lie down in the streets in Sofia. Let them march up and down and drink beer all day. The important thing is to work and produce. They don’t work and they don’t produce and they want my potatoes for two cents a pound. Let ‘em go hungry then.”

Although last year’s revolt against the Communists of Eastern Europe represented a great democratic advance for some, it also came as a shock to millions of people, and far more so in the Balkan countries of Romania and Bulgaria, on the fringes of Europe.

In Bulgaria, the changes have come almost as fallout from an explosion that happened somewhere else. Even in Poland and Czechoslovakia, where populations fought for and anticipated the changes for years, the shifts are unnerving for many. Instinctively, they know that the “new order,” whatever it turns out to be, will be anything but orderly.

Polarized, Confused

But here, nearly a year after an internal Communist palace coup toppled Eastern Europe’s longest-serving party boss, Todor Zhivkov, the country seems dangerously polarized and confused. On one side is a score of opposition groups in uneasy alliance, waiting for the old Communists to implode. On the other, the Communists have taken the reins of government. But the party, its old ideology in tatters, is divided and uncertain as to its program.

The Communists soundly defeated the opposition in June--53% of the vote--but spent the next 3 1/2 months trying without success to put together a coalition government, a period of limbo during which the old command-based economic system, facing its own uncertainties, seemed to calcify even further.

In the deadlock, many Bulgarians say they are not sure who is right. All at once, they are seeing their first real consumer shortages. People say they are afraid of what is ahead. Meat, cooking oil, sugar, laundry soap draw long lines in Sofia--when they can be found.

“The old systems simply seem to have frozen up,” said one diplomat. “You have a partially free market for food, but you still have state food-marketing monopolies that have to be supplied. One system fights against the other, holding down prices for the farmer, so no one wins. The farmer keeps his produce off the market--it’s hardly worth his trouble--and the consumers get angry at the shortages.”

The extreme of real hunger is probably unlikely in Bulgaria, although fuel shortages, electricity rationing and cold apartments are a virtual certainty for the winter to come.

For this, the Bulgarians can blame the Soviet Union, which began to demand payment in hard currency for petroleum, and the crisis in the Persian Gulf, which cut off supplies from Iraq. The Iraqis owe Bulgaria $1.1 billion, a debt run up for foodstuffs and military supplies that they had promised to pay off with crude oil.

The interrupted oil supply is a double blow for the Bulgarians: Part of the oil, refined into a variety of products in Bulgaria, was sold abroad and was a major source of hard-currency income.

A diplomat describes the coming crunch as “controlled disintegration.” He hopes the adjective, at least, is accurate. The beleaguered Socialists, even more dire, warn of “fascism” from hard-line, right-wing elements in the opposition. And some in the opposition, with ill-concealed relish, anticipate more disorder in the streets.

The most notable disorder so far came Aug. 26, when, in the midst of a noisy street demonstration, the Communist Party’s imposing headquarters in the center of Sofia was heavily damaged by fire. The most hard-line opposition leader, Konstantin Trenchev, head of the labor federation that makes up the largest group in the anti-Communist alliance, the Union of Democratic Forces (UDF), was charged with incitement in connection with the fire. He denies the charge, but not his ardor for revenge on the Communists.

“We simply have to abolish them,” Trenchev said recently. “They do not have the right to dissolve and disappear. They have to be punished. They must not be allowed to govern. Those who committed crimes must be brought to justice.”

The “crimes” he refers to are the usual range of official corruption and secret police excesses committed by the Communists in four decades of power. It is a sweeping, populist indictment, which, his critics say, is irrelevant to Bulgaria’s current pressing problems.

In Bulgarian political circles, Trenchev, with his bright-checked sport coats and white shoes, his wispy goatee, his predilection for speaking French, is regarded as an oddball extremist--and yet a powerful, almost paralyzing force. His polarizing influence and uncompromising resistance to the Communists has foreclosed any possibility that the UDF might join with them in a coalition that could ease Bulgaria’s passage to democracy.

Much of the rest of the opposition, by nature more moderate, feels hostage to Trenchev’s hard-line stance. State President Zhelyu Zhelev, a moderate former UDF leader, urged the 16 squabbling opposition groups to bury their differences and join the government. His pleas were rejected. Most of the opposition leaders fear that they would be accused of selling out their supporters if they joined a Socialist-led government.

“Our political culture is very low,” said Ruman Vodenicharov, a leader of the Bulgarian Human Rights Committee, one of the few opposition groups that predate last November’s ouster of Zhivkov. Now a member of Parliament and an advocate of compromise, Vodenicharov sees Trenchev and other hard-line anti-Communists driving a conservative and alarmed population further from democracy.

“Now we see the old system breaking down,” Vodenicharov said, “before there is something ready to replace it. The old nomenklatura-- the people who did the work--for years carried out their instructions, did what they were told and got food in the shops, and now they are being attacked in the street. We have to face the fact that we need these people now. The UDF is not yet ready to do this by itself.

“Our nation is old, demographically,” he went on. “We have 2 million retired people. We have a million former members of the Communist Party, and their families. In a country of 8 million, this is a strong base (for the Socialists). People here have not been free. Public opinion is not prepared for real change. In a sense, the people were not ready for free elections. What they see is very frightening.”

Despite the underlying tensions sensed by politicians, and the urgency faced by Prime Minister Andrei Lukanov and his newly appointed government--all reluctantly but necessarily chosen from the Socialist Party--the mood of Sofia is calm. An air of almost Mediterranean slowness prevails. Sidewalk cafes, where passersby stop for espresso served in small plastic cups, are crowded with people and noisy with conversation.

Tranquil Portrait

Residents complain that there is little in the shops to buy, yet by the standards of Moscow or of Poland of two years ago, there is relative plenty.

The city is blessed with spacious parks, the benches filling at the end of the workday and seeming to confirm the impression of a population at the older end of the chart. The portrait of Bulgaria, even from this urban vantage point, is one of tranquillity, of appreciation for conversation, fine afternoon sunshine, children at play and reliable habits of life.

“I would not say I am a Communist,” said an elderly man meeting a neighbor on a bench near his apartment. “I would not say what I am. But I have no sympathy for disorder.”

Small wonder, then, that in the countryside there is even less sympathy for the bumptious process that some Eastern European social analysts refer to as the “normalization” of political life. In the countryside, the natural conservatism of the population regards drastic change as a threat: They see no alternatives in sight.

On top of its enormous economic problems, Bulgaria faces environmental disaster. Yet even in this, people cling to the comfort of the familiar, although it may well be killing them.

About 80 miles east of Sofia, a string of small towns and villages surrounds a copper mining, ore-enriching and processing works, three foul enterprises that employ about 6,000 workers and support a population five times that size.

Foul Enterprises

The mining operation has scarred the land, and its supporting processing plants have poisoned the soil, the water and, according to some, the people.

The copper is of a notably poor grade and its processing results in an abnormally high byproduct of arsenic, which for the last 30 years has been poured directly into surrounding streams and catchment lakes. The whole complex, as is typical of such concerns in the Communist world, loses money.

Dr. Nikolai Velchev works at the main hospital in Pirdop, the site of the mine’s main processing plant, and senses that he is sitting atop a major human disaster.

“It is something normal here now for people 30 and 40 years old to be dying of cancer,” he said. “I worked here 12 years ago, then went abroad for a time, and came back three years ago. The difference between then and now is enormous. We have lung cancers and many abdominal cancers especially.

“What is most unpleasant is that it is affecting young people mostly, but of course it strikes the old as well. The Ministry of Health tries to tell us that bronchitis is common among children all over Bulgaria, but I tell them that the effect of common bronchitis is different from chronic bronchitis caused by sulfur dioxides in the atmosphere.”

The child mortality rate for the area, Velchev said, is 44 per thousand, more than double the national average. The number of miscarriages and stillborn infants is growing.

“Eighty percent of the children here have periodontia, baring of the gums, because of the arsenic. Arsenic is in the food and in the air. It is in the soil and in the water table.

“You can eat the tomatoes here for a week, and it will not hurt you,” he said. “You eat the food here for a lifetime, and, well, it is dangerous. It causes a whole series of neurological illnesses--falling blood pressure, damaged circulation, nervous disorders. The plant has been operating since 1959, and now we are seeing the results.”

In June, Velchev ran for election as a UDF candidate. Although he did not directly advocate closing the plant, he campaigned on environmental issues. It was not an attractive issue in Pirdop, and Velchev’s Communist opponent won easily.

“The problem is,” Velchev said, “that the greater part of the population works in the plant. And they have two alternatives. They can go on working in the plant, slowly poisoning themselves and their children, or go without the means to survive.”

Maternity Leave

At the front steps of the hospital, Silva Shentova, 28, rocked her six-month-old daughter in a baby carriage. Shentova was on maternity leave from her job as a mining engineer.

Yes, she said, she knew that cases of bronchitis are common among children. There are respiratory diseases, she knew, but she had no information on other illnesses. She did not believe the mine should be closed. As an engineer, familiar with the workings of the processing plant, she assumed that the problems associated with the arsenic might affect other areas more than Pirdop.

“It goes in the river,” she said of the arsenic.

The rivers, of course, are dead.

“We haven’t seen a fish in the rivers here for years,” said one of four women gathered on the steps of a food shop in the neighboring village of Zlatica, where the ore enrichment plant is located.

Together, they formed a small Bulgarian chorus of complaint, uncertainty--and nostalgia for better times.

“Three young people died here earlier this year,” one said. “Some say it was cancer, but we are not sure.”

“It was better before. At least there was cooking oil. Even chocolate.”

And no patience here for the political ferment in the capital.

“Rallies and lying in the street is stupidity--simply useless. I will butcher my cow, I will can the meat and I will get through the winter and take care of myself.”

“We are not interested in who takes power. We want a normal life.”

Farther up the road, in the mountain town of Koprivshtitsa, strings of red peppers, hanging from carved wooden porches, dry in the afternoon sun, perhaps free of the pollution from Pirdop. Koprivshtitsa’s waters, pouring from clear-running springs, are presumably safe. But here, too, the normal life seems at least distantly threatened, and people prepare as for a siege.

In essence, it is this fortress that any new government in Bulgaria, whatever it calls itself, will have to overcome if it is to modernize an economy and a mentality set in four decades of Communist concrete. However rigid, or even poisonous it seems to outsiders, it is familiar.

“Maybe some people have been afraid,” said the farmer, unhitching his pony from its wagon load of potatoes, “but for these 45 years I have seen nothing bad. Maybe some personalities used their power for money, but they are exceptions. I know how to work. These young people, they only want to strike, they don’t want to work. That is the problem.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.