Odes to an irresistible anarchist: Ernie Kovacs

“Kovacsland: A Biography of Ernie Kovacs”

by Diana Rico

Harcourt Brace Jovanovich: $19.95, 354 pp.

“Sing a Pretty Song: The Offbeat Life of Edie Adams”

by Edie Adams and Robert Windeler

William Morrow: $19.95, 320 pp.

For anyone who was around in the 1950s, when the medium of television was relatively new and hadn’t yet become altogether defined, in Robert Hughes’ phrase, as “wet-nurse to the culture,” mere mention of the name Ernie Kovacs is enough to induce a near-paralysis of reverie. The Kapusta Kid, Percy Dovetonsils, the Nairobi Trio, Uncle Gruesome, the endlessly inventive bits that teased our naturalistic assumptions about time and space as viewed on the tube, the sheer sense of fun and gentle play that emanated from a Kovacs show, were wholly innovative then — and unmatched since (though the Monty Python troupe has come close).

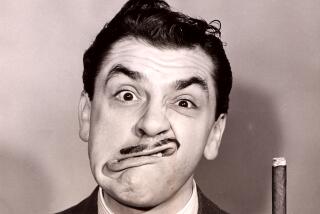

At the center of an improbable world stood an improbable figure, a tall, soft man with a low, fond voice who smoked a big cigar, wore a vivid mustache, and whose eyes seemed forever fixed at the molten edge of a sweet Hungarian melancholy.

It’s been nearly 30 years since Kovacs was killed in an auto accident in Beverly Hills, and though there’s been a resurgence of interest in his life and times over the past decade — ABC television produced the 1984 “Ernie Kovacs, Between the Laughter,” and in 1987 he was inducted into the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences Hall of Fame — there’s been almost nothing of substance written about him.

Suddenly we have two books: Diana Rico’s “Kovacsland” is the more formal and detailed biography, with notes and appendixes; Edie Adams’ autobiography, while revealing a woman of talent and conviction, does nothing to begrudge his place at the center of her life for as long as they knew each other.

Both offer the biographical details of Kovacs’ difficult start in life — he was born in Trenton, N.J., in 1919 to Hungarian immigrant parents. His father was a bootlegger and restaurateur, which gave the young Ernie a taste for the high life that never was to leave him. His mother was an implacable scold who grew worse as time went on and never relinquished her grip on him even after he was married (she defied a court order by insisting on moving in with him and his family). He nearly starved while studying acting in Manhattan. Later he came down with pleurisy and pneumonia, and, owing to a medical mix-up, tuberculosis, all of which kept him confined for 18 months in a Welfare Island hospital.

Rico gives an excellent thumbnail history of radio days in America, before Kovacs joined up with WTTM in Trenton as a disc jockey. In nearly no time he began changing the format to suit his penchant for anarchy and playfulness. He’d set fire to a news announcer’s script; once he lowered a rubber spider on a string in front of a singer as she was performing--she screamed on the air. In late 1949, he went to work as a staff announcer for WPTZ-TV in Philadelphia, and in March of 1950, with five minutes’ notice, went on the air to host a cooking show called “Deadline for Dinner.”

In those days there would often be lots of time to kill, a perfect condition for Kovacs’ love of invention. (Edie Adams, a fledgling singer from Tenafly, N.J., who was added to “Three to Get Ready” — the first TV morning wake-up show in America — also learned to wing it when Kovacs often arrived late to his own show.) He, and the medium, were growing up together; as his reputation expanded, so did the number of stations that hired him and the fans he picked up along the way. By the time he left New York for Hollywood in 1957, he’d worked for CBS, NBC, ABC and the Dumont network — sometimes for more than one at the same time.

While “Kovacsland” ably places him in a historic and cultural context, “Sing a Pretty Song” offers a more intimate insight into the life of Ernie Kovacs.

Edie Adams was a highly disciplined and resourceful young woman with a developing theatrical career of her own before she met Kovacs. (She would later win a Tony Award for her role as Daisy Mae in “L’il Abner.”) Although her book is somewhat uneven in the scope of its detail (as Rico’s book is occasionally tentative when it doesn’t have details to lean on), it’s a straightforward story of an unavoidably difficult emotional life. She owns up to having failed his two daughters by a previous marriage (one of the most harrowing periods in Kovacs’ life was when the girls’ mother kidnapped them and hid them in Florida). Kovacs was unquestionably the love of Adams’ life, but also the source of her greatest pain — until the death of their daughter.

Kovacs hated New York, but never enjoyed the brilliant screen success in Hollywood that he had had in television in the East. He was an extravagant, compulsive gambler. His battles with network brass and sponsors became more pitched. The IRS swept in to take 90% of the money he made. In both books, the sense of his mounting exhaustion and desperation becomes increasingly palpable so that, by the time he slipped behind the wheel of his Corvair that rainy night in January of 1962, he seemed to be an accident waiting to happen.

“Kovacsland” and “Sing a Pretty Song” complement each other well, and let us warm again to this brilliant, impossible, endearing, lovely man.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.