Safe Passage : Daily Maintenance Checks Ensure the Rides at Magic Mountain Provide Thrills, Not Spills

It’s thrillsville, unplugged.

In the first moments of daylight, the Colossus is frightening only for its eerie silence. Below, Magic Mountain is a litter-less wasteland of lifeless thrill rides, surrounded by empty parking lots.

Then Mike Rowbotham enlivens the morning.

Klunk! Rowbotham drops a wrench from his perch atop Colossus. Klank! It bangs off a wooden crossbeam, then clatters and bangs down 100 feet through the huge roller coaster’s intricate skeleton, landing with a metallic thud among the old baseball hats, cups and pennies underneath.

Rowbotham laughs. “You only drop ‘em when you’re way up high,” says the carpenter who, for 11 years, has arrived before dawn to tighten the nuts and bolts of a delicate illusion, making sure that rides designed to scare the bejabbers out of people are as safe as the mechanical ponies outside K mart.

“Magic Mountain is strictly a thrill park,” says Courtney Simmons, the park’s public relations manager. “We don’t deal in fantasy lands--we’re here for the hard-core fan.”

What Southern Californian has not been exposed to the villain-voiced radio announcer growling about the Viper (everybody now), “the most frightening roller coaster on Earth” and its hurling speed, seven loops and drop from 18 stories high?

But truth be told, a 2 1/2-minute ride on Viper is safer than the freeway drive to get there.

“The thing is, how do you make somebody feel their life is in danger when it isn’t?” says Doug Soucy, assistant manager in charge of electricians.

Answer: You work on the illusion.

“Safety is our No. 1 concern,” Simmons says. “If it wasn’t, we’d be out of business. . . . People will slip on their own spit and sue this park. I guess that’s the kind of world we live in.”

So the preventive maintenance crew goes to work. It’s a morning ritual any kid worth his high-tops has fantasized about: Each morning, Rowbotham and 35 other carpenters, electricians and mechanics slip into the empty amusement park to climb up, over, under and around this giant playground of rides, checking for loose bolts, weak wood, cracks and flaws.

Among themselves, the crews refer to the rides as roller coasters and “flat rides,” or, more affectionately, “spin and barfs.”

But Soucy speaks of roller coasters like fine wine; he enjoys the nuances no one notices in the curves and dips. He fondly looks up from beneath the trademark loop of the 14-year-old Revolution roller coaster, the first one to turn riders upside-down.

“Isn’t it pretty?” he sighs.

The rest of the park is also a collection of “firsts” and “biggests.” Colossus, built in 1978, is the biggest dual-track wooden roller coaster. Ninja, built in 1988, is heralded as the only suspended roller coaster on the West Coast.

And there is Viper; the synonymous-with-thrill Viper; the roller coaster talked about in every office, schoolyard and roller coaster aficionado newsletter in the land. Undergoing special track repairs this morning, its red tracks glimmer out on the park’s edge.

At its highest, Viper is 18 stories--ho-hum to the carpenters and mechanics who climb it.

This park is legendary for its hardware--rides that aren’t gussied-up to appear as magical or otherworldly. For the guys who bring them to life every day, there is a fond attachment to all this concrete and steel.

But beneath the macho, they get a kick out of riding the rides, too.

“My favorite one is always the newest one,” Soucy says. From a vantage point atop Revolution, surrounded by the lush trees that have grown up around the coaster and looking out over the park, he recalls that he had left Magic Mountain a few years ago to work as an electrician in the Real World.

“I came running back,” he says. “And they keep building new roller coasters.”

Public relations manager Simmons steers her car through the desolated amusement park, past the vacant stares of Foghorn Leghorn and the cherubs that adorn a darkened merry-go-round (“It’s like driving through a creepy, closed shopping mall”), searching for the coaster jockeys dutifully inspecting the overgrown toys.

“I saw a guy the other day walk up Colossus with a cup of coffee in his hand . . . that’s how well these guys know these roller coasters,” she says.

There has been one death on Colossus since its opening. In 1978, Carol Flores, 20, was killed when she was thrown from the ride. While the park was eventually found not to be responsible for Flores’ death, the incident prompted more safety measures on the supercoaster and other Magic Mountain rides.

From afar, Rowbotham and his two partners look like bugs atop the 115-foot incline of the $9-million ride. From their perspective, the park below looks not unlike the free map given to customers.

The sun gets higher and starts to peep through the clouds. Bit by bit, the park comes to life. The wind whistles through the beams and each step is precarious. As they hammer a few bolts back into place along the way, Rowbotham pulls out a cigarette and smiles. “No fear, just hard work,” he says.

“We have a motto,” says mechanic Mike Woods as works on the air brakes of Freefall, the giant L-shaped ride that simulates a 10-story plummet. “It’s ‘I’m not falling.’ ”

Suddenly, the tune of “Mexican Hat Dance” blares from loudspeakers--and then slows to a stop. And then starts again.

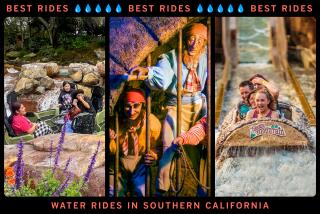

The rides wake up. Water begins to spurt through the Tidal Wave, the flat rides begin to whirl.

And at the front gate, hundreds of eyes peer into the empty park, waiting for the 10 a.m. opening.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.