Soccer Language : AYSO Coach Hector Mendoza Teaches How to Win, Mexican Style

Hector Mendoza, a native of Mexico’s Pacific coast, can’t recall exactly when he came to live in this country.

“I think maybe 13, 14 years ago,” he said in English heavily affected by his native tongue.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. Dec. 3, 1989 For the Record

Los Angeles Times Sunday December 3, 1989 South Bay Edition Sports Part C Page 21 Column 1 Zones Desk 2 inches; 69 words Type of Material: Correction

Youth Soccer--A recent story mentioned that a boys’ all-star team from Redondo Beach Region 34 of the American Youth Soccer Organization had the best finish of any team in the region’s history when it finished second in the state last year. According to Region 34 officials, who supplied the original information, the boys fared better than any all-star team that region has had. Three divisional teams, two girls’ and one boys’, from Region 34 have won state age-group titles in the past.

Organizers of South Redondo Beach Region 34 of the American Youth Soccer Organization say Mendoza, a volunteer coach, often leaves the details to speculation and lets others blame the language barrier.

“It comes in handy, especially when dealing with parents,” said Judy Deierling, whose son, Adam, plays for Mendoza on the undefeated Los Gatos Negros team.

When it comes to coaching soccer, however, Mendoza and his charges speak the same language.

A resident of Harbor City, Mendoza is rapidly becoming one of the South Bay’s finest age-group instructors, an architect of raw talent. Last year he guided the region’s 10- and 11-year-old boys’ all-star team to a sectional title and into the Southern California championship game, where it lost, 1-0, to Buena Park. It was the highest finish by any age-group team from Redondo Beach.

Jim Zelenay, a region official, says Mendoza is already a legend. “He lives for soccer.”

Given the Latin passion for passing the ball, Mendoza, who played in Mexico’s semipro league for 10 seasons, teaches a style most Anglo teams have difficulty with--one that requires an inordinate amount of conditioning.

“Run, run, run. I give them lots of exercise,” Mendoza said. “I teach them how to pass, kick and control.”

Said Judy Deierling: “His teams are second-half teams. It’s not that Hector’s teams come on stronger; it’s that other teams just run down. His keep going.”

He’s also good with futbol egos: “There are no glory hogs here,” said Team Mother Evelyn Angelone. Her son, Paul, is a sweeper for Mendoza.

A distinctive Latin style of play was evident in the precision foot-passing by the black-and-orange-shirted Los Gatos Negros (Black Cats) at a recent game. The team, undefeated in boys’ Division 3, is made up of 12- and 13-year-olds.

Said region Commissioner Kathy Thomas, “His teams definitely play that Latin style: dribble and pass, dribble and pass.”

Differences in futbol style and philosophy usually follow ethnic lines worldwide. Burly Europeans, for example, prefer a harder-charging, more aggressive approach. Latins, who are usually smaller, prefer finesse.

In the United States, different soccer styles confound average sports fans, most of whom spend their weekends watching American football, not soccer. Internationally, developing a style has been an obstacle for the current U.S. national team, which defeated Trinidad and Tobago, 1-0, on Nov. 19 to qualify for the 1990 World Cup. The United States will host the World Cup in 1994, but without the support of its countrymen, the event will struggle here.

All that hasn’t been lost on Mendoza, who is proving that Americans can succeed in soccer if they develop style. AYSO rules insist that every player on a team play at least a half. Stacking of rosters with premier players is forbidden. To Mendoza, those rules are superfluous.

“He plays with whatever he gets, and he still wins,” said Judy Deierling. Los Gatos Negros defeated a well-respected private boys’ club team from Manhattan Beach earlier this season.

“Every kid wants to play for Hector,” said Deierling. “If they make Hector’s team, they think they have it made.”

Mendoza has instilled his style by scheduling several games with a Mexican team in Ensenada over the Thanksgiving weekend. The trip is the third time a group of boys from Redondo Beach has crossed the border to play soccer. Mendoza says he wants to add more games with teams from mainland Mexico and La Paz to give his players what he says American children lack: exposure to international play.

“Five or 10 more years, and soccer will be very powerful here,” Mendoza said. “There are some really good players here. The U.S. is going to be very good.”

Adam Deierling, a center halfback, recognized the benefit of playing Mendoza’s game when he was only 8.

“I played against the team he was coaching, and I realized he was a really good coach,” he said. “They passed a lot and controlled the game.”

Mendoza isn’t cut in the mold of the stereotypical American Little League coach, either, parents say. On the sidelines at a recent game at Alta Vista Park, Mendoza was rather laid-back, choosing only to offer a few instructions to his players.

“He’s not the kind to yell and shout at the games,” said Judy Deierling, a league secretary. “He does his coaching in practice and lets the kids play the games.”

Thomas says Mendoza’s practices differ from those held by Anglo coaches.

“He gets right out there and plays with the kids,” she said.

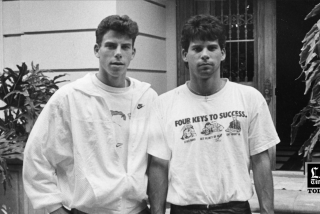

In fact, Mendoza, 34, could almost pass as one of the players, with his boyish grin and easy demeanor. He’s still active as a player too, in a predominantly Mexican-American league that plays in Los Angeles and Orange counties.

As with most of his countrymen, Mendoza crossed the border in search of a better life.

“There’s not a lot of money (in Mexico),” he said.

He came to Southern California on the advice of his mother, Susanna, who has also resettled here. Mendoza got a passport and moved first to Lomita, then to Harbor City, where he took a job in a ceramics factory. He now works for an auto repair company.

Seven years ago, Mendoza and his wife, Antonia, were at a carnival in Redondo Beach when he saw a booth advertising soccer sign-ups. The couple’s oldest son, Hector Jr., now 12, was eligible to join the Kindergarten Division, and Hector Sr. jumped at the opportunity.

“It was a big fiesta, with big parade. I wanted my kids to play soccer,” said Mendoza, who has three sons.

A year later Mendoza wanted to coach, but “I don’t speak very good English.” He wound up assisting on Hector Jr.’s team. Antonia, who is fluent in English, translated for him.

“Nobody (understood) me at the time,” Mendoza said. “I just (pointed).”

Gaining confidence in his English, he headed his first team in 1985. Since then, he has also coached a women’s club team, but he discontinued that because “I (don’t) have that much time.”

He has found a home, however, in AYSO Region 34, where, Mendoza says, “it’s open play. Everyone can play.”

“I get different kids each year. I teach them best I can. I think (they) all enjoy.”