A New Love Story : Olga Connolly, Once the World’s Darling, Is Giving Something Back

There was no shortage of drama at the 1956 Summer Olympics in Melbourne, Australia.

Five countries boycotted, either because of the Soviet Union’s invasion of Hungary or the tension in the Middle East over the Suez Canal. Hungarian athletes hauled down their flag in the Olympic Village and tore off the Communist emblem. A water polo encounter between the Soviets and Hungarians had to be stopped because of violence.

Yet, if a movie were made about the 1956 Summer Games, it might well be a romance. Adding a touch of warmth to the Cold War, an American hammer thrower, Harold Connolly, and a Czechoslovakian discus thrower, Olga Fikotova, both gold medalists, met in the Olympic village and became infatuated.

The world was captivated by their story, so much so that the Czech government, despite its objections, could not resist when the dashing Harold charged into Prague a year later, married Olga and carried her back to the United States with him.

The day after the wedding, The New York Times editorialized: “The H-bomb overhangs us like a cloud of doom. The subway during rush hours is almost impossible to endure. But Olga and Harold are in love, and the world does not say no to them.”

This, of course, is when the credits begin to roll.

But life goes on.

The Connollys were married for 16 years and had four children before their divorce in 1973.

Harold, 57, who is now married to another Olympian, the former Pat Daniels, recently left his position as assistant principal at Santa Monica High School and moved to Washington, where he works for the Special Olympics.

Olga, 56, who has not remarried, still lives in Culver City in the last house that she shared with Harold.

Olga, Harold and Pat occasionally are invited to functions, where invariably someone refers to Pat as Olga, and the love story becomes one of the main topics of conversation, embarrassing all three.

“We don’t want to hear all this nonsense about an Olympic romance,” Olga said last week at her home. She was suffering from the beginning stages of laryngitis, but she declined an offer to postpone the interview. She has so much to say. And to write. And to do.

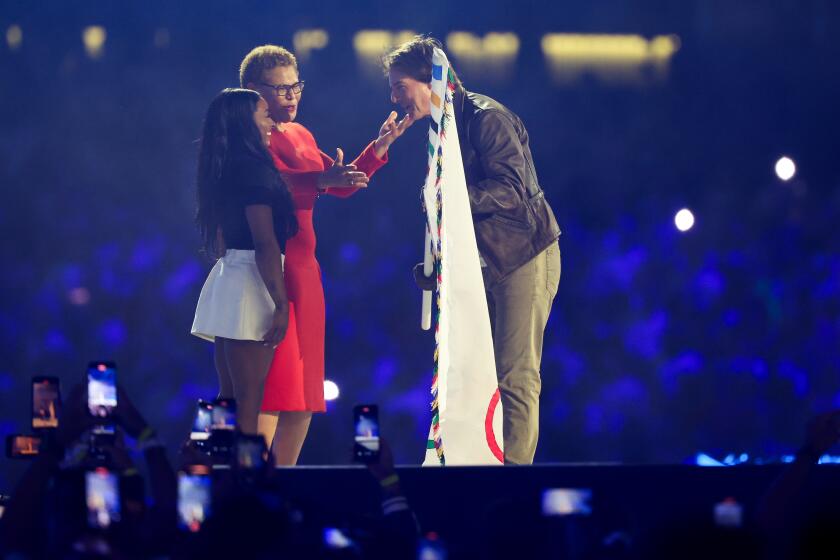

She said that she would rather be remembered as a five-time Olympian, all but the first as a discus thrower for the United States, and as the U.S. flag bearer during the opening ceremony for the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich.

Her teammates elected her to carry the flag over the protests of U.S. Olympic Committee officials, who had considered removing her from the team because of her outspokenness until Sen. Alan Cranston (D-Calif.) came to her defense.

The issue of the day then was the U.S. involvement in Vietnam, which she opposed. In a New York Times interview, she called upon Richard Nixon to cease the bombing during the Olympics.

After the opening ceremony, a USOC official sarcastically congratulated her for doing such a perfect job of carrying the flag despite her anti-war views.

“In Czechoslovakia, I learned to march,” she said.

Causes have changed, but she has not.

She is a feminist and an environmentalist who also speaks passionately about animal rights and youth development. For much of her post-competitive life, she has been involved in the latter as a social worker for various agencies.

Since social work does not pay significantly better than discus throwing, she also tried temporary secretarial work, which indeed was temporary in her case.

“I’m such a lousy typist,” she said. “I have a talent for changing things. I’d work for a place for a couple of days, and I’d be saying that they should do things differently. They didn’t want to do things differently. They just wanted me to type a letter without a mistake.”

In her living room are pictures of her children. Also prominently displayed are some of their athletic awards. Three of the children are actively involved in sports: Mark, 28, as a Golden Gloves boxer in Nevada; Jim, 25, as a decathlete in Los Angeles and Mereja, 25, as a professional volleyball player in Italy.

Another daughter, Nina, 22, a talented singer, married just out of high school and provided Olga with the joy of her life, a grandson, now 2.

But there is only a single picture of Olga on the wall. Wearing Jim’s U.S. track uniform, she could pass for one of his teammates in the picture. At 5 feet 11 inches and 138 pounds, she still appears athletic.

She has her arm around a proud young boy. Earlier, he had been despondent after losing in a 100-yard race. But when Connolly discovered that his shoes were too large, preventing him from getting a good start, she arranged for him to have a new pair of sneakers and persuaded the organizers to allow him to run the 440, which he won.

Today, Connolly is the supervisor of preschool and senior citizen programs at San Pedro’s Toberman Settlement House, which is funded largely by the United Methodist Church and United Way. Issues affecting seniors are relatively new to her, but she has adopted them as vigorously as her other causes.

She said that on the first field trip after she joined Toberman, she took the senior citizens to a club to see comedy and magic acts.

“Their previous field trips had been to do things like getting their blood pressure checked,” she said. “I thought that was a little uninspiring. I wanted to make them feel alive.

“Senior citizens have been stereotyped as feeble and dependent by commercial and other interests who offer them services. Of course, there are seniors who are ill and incapacitated, just as there are ill and incapacitated young people and middle-aged people.

“But nearly all of the mail I get on my desk is literature about convalescent homes or preparation for funerals. I’m not saying these services aren’t useful, but seeing this sort of thing becomes a daily routine for seniors, and it beats them down.

“The group I work with is a hell of a tough group. I’m their supervisor, but I wouldn’t dream of telling them what to do. If they need a consultant, I’m here. I respect these people. “As a society, we will begin recovering when we start respecting the knowledge of the people who have retired after working their butts off all their lives and now have something to say. This second childhood stuff, that’s nonsense. We should treat them as senior officers.”

After returning home from a day of work in San Pedro, Connolly often writes. She sometimes begins at midnight and does not stop until 6 a.m.

She has written one book, “Rings of Destiny,” which is about the 1956 Summer Olympics and her romance with Harold, and she co-wrote another with Harold about Finland, where they lived for a while in the early 1960s.

She has written essays on various topics, including fishing. Most of her work that has been published in newspapers is about the Olympics. She is concerned for the movement, arguing that it has sold out its ideals to politics and commercialism.

For example, she told the story of her first meeting with the Soviet Union’s Nina Ponomaryeva, who won the discus competition at the 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki.

Having become a discus thrower after spending her formative years as a basketball and team handball player in Czechoslovakia, Olga, 22 at the time, competed in her first international track and field meet in 1955 in Poland. Out of 28 throwers, she finished 28th.

While working out the next day, she was approached by Ponomaryeva.

“One thing wrong is that you are too skinny,” Ponomaryeva told her. “You really don’t know what you’re doing.”

Ponomaryeva volunteered to work with her. Sharing the techniques she learned from her coaches in the Soviet Union, she gave Connolly the foundation that she was lacking.

“She told me that if I followed her advice, she would see me the next year in Melbourne,” Connolly said.

Indeed, she did. Connolly won the gold medal in Melbourne. Ponomaryeva finished third.

“That wouldn’t happen today because of the money in track and field,” Connolly said. “If you told someone your secrets, they might win and take money away from you. There’s been a loss of cooperation.”

So Ponomaryeva took it well when Connolly beat her?

“No,” Connolly said, laughing. “She was mad as hell.”

Three weeks later, as Soviet and Czech athletes shared a train across Europe, Connolly caught a bad cold. Ponomaryeva heard about it and brought her a potion that she insisted would cure colds.

“It tasted awful,” Connolly said. “It was so bad that I got better so that she would quit bringing it to me. But we became very good friends.”

Years later, Harold and Olga named their youngest daughter after Ponomaryeva and another woman named Nina from Czechoslovakia.

Although it would have been a good human interest story for reporters, the friendship between Connolly and Ponomaryeva was submerged amid the worldwide publicity generated by Harold’s courtship of Olga. Sean Penn and Madonna were hermits by comparison.

“It was a great romance, a great infatuation that grew,” Olga said. “But I’m not sure if it was true love.

“I was the first Olympic champion that year in track and field, and Harold won his gold medal on the second day. I was definitely not the stereotype of the Eastern Bloc woman athlete that he imagined. Harold was enchanted by that. And I felt that the Americans had such freedom. Everybody was being such an individual. I was a person like that, and that appealed to me very much.

“The Czechs made such a big thing of it by criticizing me for the romance. They wanted us to end it, and that made me angry. So now there was a little rebellion in it. It was very romantic.”

But the romance did not last. After several years of marriage, Connolly said that she realized that she and her husband had grown apart.

“I never had any intention of going to five Olympic Games,” she said. “I wasn’t that committed to it. But Harold truly loved athletics. He was basically married to the hammer. He broke nine world records after we got married.

“We went through 16 years of marriage because of mutual respect and camaraderie. But we had different interests. Eighty out of 100 people in our situation might have stayed together, but to really be in love is a very rare thing. When you really are in love with somebody, they totally and inescapably become part of you.”

She said that she has remained friends with Harold and his wife, Pat, and that they talk occasionally on the telephone, mostly about athletics. Pat has coached several world-class athletes, including Evelyn Ashford.

“When Pat and Harold met, they found real love,” Connolly said. “They have a wonderful life and a wonderful love. They are one together. Harold and I were two.”

Asked if she had ever found true love, Connolly said that she had.

“But it didn’t work out,” she said.

She did not seem sad when she talked about it. After all, she has her children, her grandson and an entire world that needs her care.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.