Going the Extra Steps to Experience the Best Cognac

Brandy is wine taken one step beyond. Cognac is brandy to an Nth degree, and the differences are significant.

Merely distilling wine gives you raw alcohol, and aging it in wood makes it brandy. Some of it can be very fine indeed. Aged in wood for a decade or more, the rough, fiery liquid turns amber and assumes a smoothness that no other process can attain.

But, when the best grapes are chosen and the distilling process is slowed down to an art, when oak aging is done carefully and blending done, superior brandy is achieved.

In Cognac, that is generally the system, and we are familiar with the most popular names. Hennessy, Mumm, Courvoisier, Martell, Remy Martin.

And then there is Delamain. And, one might argue, Germain-Robin.

Cognac, as great as it is, is not as it once was. And the reason is that time is money, and great Cognac demands time in oak casks, mellowing.

Age vs. Quality

In the last few years, many of the larger Cognac producers have chosen to release to market Cognac of lesser age. Is it of lesser quality? The smaller, more time-oriented producers would have you believe so, and a recent evaluation of some of the superb Cognacs of Delamain showed me again why I cleave to the products of this small cognac house.

First, however, a bit of background. A problem with any higher-alcohol beverage is the alcohol: It can burn and produce a harshness in the mouth and throat that is unpleasant. Time in oak has a way of curing this by smoothing out the rough spots, taming the beast.

Moreover, Cognac made in the small district called Grande Champagne offers the most finesse and requires the longest time to come around, so anything called Grande Champagne costs more on two counts.

Many of the established firms with large production and worldwide demand are using slightly younger Cognacs, and the result is less development and less complexity.

Delamain uses only Grande Champagne distillate and ages it very carefully with the aim of making blends that fit a house style more delicate than most. Over the years, I have found Delamain to be more to my liking than almost all other Cognac because of its more fragrant intensity, its depth and above all its delicacy.

But Delamain is not cheap. The least expensive of the Delamain line is the bottling designated Pale and Dry, which sells for $42. However, because it is not as well-known, this Cognac sells for less than $30 in some discount shops. Up the scale is Delamain Vesper, $65 and often seen about $55. Top of the line is called Tres Venerables, an incredibly smooth and intense experience worth the $100 price tag. I have not seen this discounted much below $90.

(A very rare bottling, designated Reserve de la Famille, sells for about $250, but so little of it is made that it’s mentioned here only for those who’d like the ultimate experience. This Cognac is woodier and richer than the Vesper, which is more intense in some ways. The Reserve is quite something.)

Because of its uniqueness, Delamain requires hand-selling, and for that reason one Southern California wholesaler has chosen to market it through its wine division, not the more traditional spirits division.

That tactic is valid, I was told by a well-regarded Cognac retailer, who said that he doesn’t worry about people stealing Delamain off his shelves because once stolen it can’t be disposed of (i.e., sold) anywhere near as readily as the better-known brands.

“The more publicized brands have to be kept under lock and key because the perception is that they are better--because they’re more widely seen.”

He said a Cognac as fine as Delamain or his favorite, Privelege (which sells for $160 a bottle), won’t fetch as much on the black market as a brand that advertises more heavily.

The producers would tell you that Cognac is unduplicatable. And so it may be. It is produced from wine made from the poor-quality Ugni Blanc, Folle Blanche and Colombard grapes, and thus is locked into a formula.

And for that reason, they argue, other brandies (which use other varieties) taste different. And though that’s true, Hubert Germain-Robin believes that it’s possible to produce great Cognac-style brandy in a region other than Cognac.

Germain-Robin Fine Alambic Brandy is the result. The fourth release of this limited-production item is now out, and it’s the best version yet of a Cognac-style brandy from California.

A Ride to Success

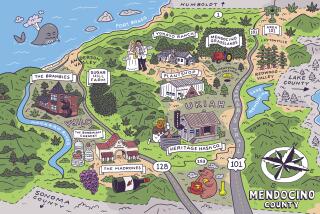

Located on a ranch in a remote region of Mendocino County, the Germain-Robin distillery is a joint project of Hubert, a Cognac expatriate, and Ansley Coale, who earned a doctorate in Greek and Roman history and who picked up a hitchhiking Germain-Robin one day in 1981 on U.S. 101 south of Ukiah.

Coale was teaching at the University of California in Berkeley at the time, and he had also made a living restoring old homes. But he wanted to move permanently to his 2,100-acre sheep ranch in Mendocino County. The meeting led to a partnership.

Lot 4 of the Germain-Robin alambic (pot still) brandy shows some of the delicacy that Delamain achieves. There is more of a wine-like sort of aroma, more intense in ways than the Delamain Pale and Dry, but its smoothness is rather astounding since it’s achieved from less than 6 years in oak barrels.

Coale points out that that can be done because Hubert has broken away from the French formula and uses grapes such as Gamay and Pinot Noir in the base wine. Also, he varies the temperature of the initial fermentation, does the distillation much more carefully than in the larger Cognac houses, and removes with extreme care the first and last portions of distillate--called the head and the tail in Cognac.

In tasting Lot 4 against Lot 5, which won’t be out for another year, I noted a significant shift in style with Lot 5, toward more elegance still. Coale pointed out that the ability to use different grape varieties in the wine from which the distillate is culled makes a major difference.

“This product has to be hand-sold,” said Coale, virtually mimicking the remark made to me two months earlier by Alain Braastad-Delamain as he toured California on a sales trip.

To achieve such sales, Coale carries with him not one of the more famous but less inviting Cognacs as a comparison. Instead, he carries with him a bottle of Delamain Pale and Dry, a most worthy competitor. “I think they compare in terms of style,” he said.

Similar Style

Tasting them side by side, I found I liked the Pale and Dry better. But the style of the two products was similar, and since Germain-Robin sells for $28 (discounted to about $24.50), it’s a good buy.

Germain-Robin trained as a Cognac producer for his family’s Cognac facility in France, Jules-Robin & Cie. He left that business after his father sold the operation to the French giant Martell.

He said recently that he knew he’d have to make a choice after Martell took control and began changing the Jules-Robin production facility to one of modern techniques, aiming at streamlining the operation. He said the new concepts didn’t allow for as much personal, hands-on control.

Mass methods were substituted for the slower, finer methods of distillation, he said. The small 250-gallon alambic (pot) stills were replaced with giant stills handling 10 times that amount. Huge aging vats replaced the standard 96-gallon barrel in which the distillate aged.

“Things were not the same, and I wanted to find a place where I could make great brandy,” he said, so he left France and began touring the cooler climates of Northern California.

His chance meeting with Coale led to a meeting of minds, and the brandy project was born.

At Germain-Robin, a wide variety of grapes are all distilled separately and aged in barrel separately until a final master blend is made.

“It’s interesting to work here because no one tells you what grapes you can use. You can use any kind of grape you want, so you can be creative,” he said.

The first release of Germain-Robin Fine Alambic Brandy was put out nearly three years ago. There were only 100 cases of Lot 1, which was interesting for its mildly herbal aroma. Lot 2 was smoother and a bit more woody, and Lot 3 was significantly improved for its more Cognac-like quality.

Today, about 1,000 cases are made a year, and in addition Germain-Robin is “playing around” with distilling pears, strawberries, raspberries and even making small amounts of Mistelle, in which brandy is added to unfermented grape juice to make a sweet after-dinner drink.

A reserve brandy is to be released next year.

Wine of the Week: 1986 Villa Mt. Eden Zinfandel ($8.50)--Strawberries, hints of pepper, cinnamon and cedar, and a softness that belies the great strength in this wine. Aged in French oak, this delightful first effort by Villa Mt. Eden with this variety is stunning evidence that a wine can be luscious when it’s released and can also age beautifully. If more Zinfandels tasted this good, there’d be a stronger swing back to red wine from this variety.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.