An Invitation to More Than Ever Love Christ

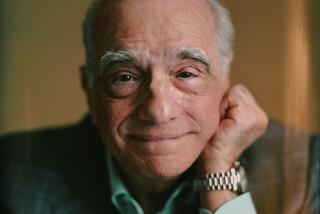

Lost in the uproar over the showing of “The Last Temptation of Christ” is the fact that film maker Martin Scorsese, novelist Nikos Kazantzakis and their critics all have adhered to the basic dogma of Christian orthodoxy: that Jesus of Nazareth was in some unique way not shared by ordinary humans, both mortal and a god. Even the traditional scriptural interpretation portrays Jesus as displaying genuine human frailties and feelings--anger, fear, doubt, self-pity, sorrow and so on.

But extremists have tilted the scales so drastically to the “god” side that his human qualities have virtually disappeared. Many, in protesting Universal Pictures’ decision to release the film, have said that “the sinless one” could not possibly have thought about sex with a woman, since thinking about it is as sinful as doing it. (It is always instructive to discover the restrictions that human dogma imposes on its gods. In this case dogma denies to God the Son what it requires of God the Father.)

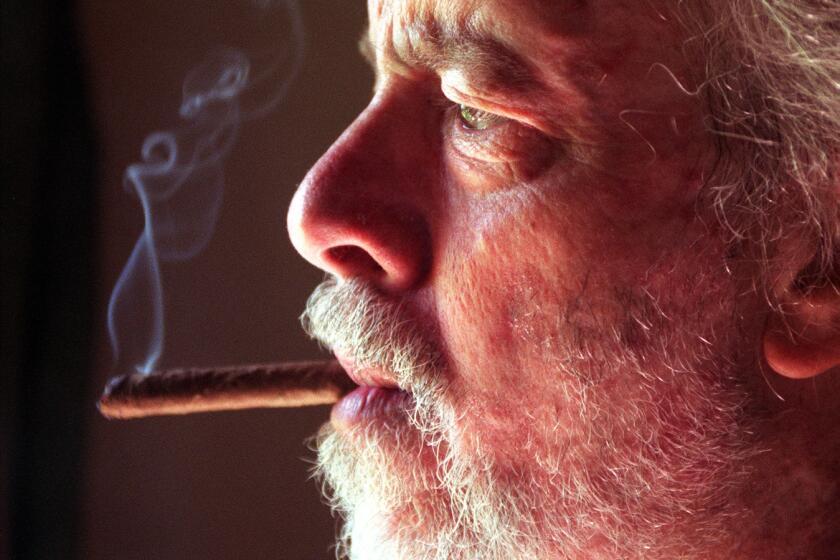

Traditionalists like Kazantzakis, who died in 1957, disagree with this view of Jesus as devoid of “real” human characteristics. How can you say Jesus “sacrificed” his life, they ask, if he had no attachment to life, experienced no doubt or pain or terror at losing it? If he had no genuine human temptations, how can he be a meaningful model of resistance for those who are tempted?

All these questions exist in a shadow world where no acceptable evidence exists, where the “truth” of an opinion depends on the intensity with which it is held, and the self-righteousness of critics is proportional to their ignorance of the works that they condemn. Granted, it is difficult (and perhaps hasty?) to judge a film before its release. But Kazantzakis’ book has been around for 30 years; surely those so quick to protest the movie could have scanned his eloquent prologue to find out what he had in mind, or the final few pages containing the scenes that have thrown them sight-unseen into such a towering snit.

While working on the book, Kazantzakis wrote that “I never felt the blood of Christ fall drop by drop into my heart with so much sweetness, so much pain . . . .” He expressed the hope that those who read the book will “more than ever before . . . love Christ.”

In the “blasphemous” passage, he portrayed Jesus as momentarily losing consciousness between the poignant cry of human agony, “Eli . . . Eli . . .” and the despairing question that follows it. In the lapse he has a vision “sent by the Devil” in which he is permitted to escape from the cross and live as an ordinary mortal. He encounters Mary Magdalene, who is promptly murdered by a self-righteous mob. Later he settles down with the sisters Mary and Martha to raise a family and live as a contented village rabbi.

Then consciousness and pain return, and he realizes “with a wild, indomitable joy” that he has not betrayed his faith. He is still on the cross: His disciples are still proclaiming the “Good News” and . . . .

“He uttered a triumphant cry: ‘IT IS ACCOMPLISHED!’

“And it was as though he had said: ‘Everything has begun.’ ”

A century ago American freethinker Robert Ingersoll commented that a lot of people who think they are very pious are really only dyspeptic. Today I suspect he would be inclined to observe that a lot of people who think they are god-fearing are merely scared silly of sex.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.