CBA Finds Way to Earn Respect : NBA Gives Its Distant Cousin a Hand, but This League Is Still the Minors

Unlike the National Basketball Assn., there are no million-dollar contracts, holdouts or incentive clauses. And instead of caviar in Boston and New York, it’s more like grilled-cheese sandwiches in Rochester and Pensacola. Ever try to take in a first-run play in La Crosse, Wis.?

Yes, if it’s Biloxi, Miss., it must be the Continental Basketball Assn., a league that serves as a holding pattern for top college draft picks who never made it and NBA players who somehow lost it.

It’s a purgatory existence but the CBA offers a place for a player to develop or rediscover his skills, prove his worth and for a few wayward souls, atone for the past.

And maybe, just maybe, make it to, or back to, the NBA.

“There is absolutely no reason to be here unless you want to move on to the NBA,” said Brad Wright, formerly of UCLA, who is in his second year with the CBA’s Wyoming Wildcatters.

“When I was up with the (New York) Knicks I made more money in one day than I make here in one week. There are no guaranteed contracts, retirement plans, nothing. What this league is good for is to improve your skills and possibly get a chance to make an NBA team in a couple years.”

A starting forward his senior year on UCLA’s 1985 National Invitation Tournament championship team, Wright was Golden State’s second pick in the NBA college draft. When contract negotiations broke down, Wright went to play in France for a six-figure salary. Only problem was, his employers failed to pay him.

He returned to Los Angeles and began an apprenticeship in broadcasting under Fred Roggin at KNBC-TV. But Roggin, among others, advised Wright to give basketball another chance--that he could always become an announcer.

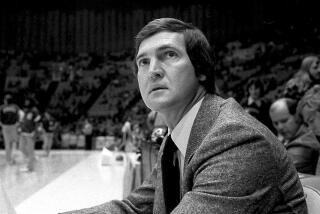

That’s when former NBA player Cazzie Russell, the coach of the Wildcatters, gave Wright a call.

“I said, ‘Here’s a guy who is 6-11 and he wants to be in broadcasting? Give me a break,’ ” Russell said.

So Wright became a Wildcatter.

“It was a tough move going to the CBA,” Wright said. “Coming out of UCLA, I had high hopes and I had heard bad things about the league, like 14-hour bus trips to get to a game. But it isn’t like that anymore.”

“My first year at Wyoming, we rode everywhere in luxury buses. The only time we saw an airplane is when we looked in the sky. But this year we fly everywhere that’s over a two-hour drive. We get good-sized crowds, at least as many as the Clippers. And the arenas we play in are first class, not high school gyms, like I heard. I can compare everywhere we play to Pauley Pavilion and I consider that my home.”

Wright was one of nine CBA players called up to the Knicks last season. Under a joint agreement, an NBA club can sign a CBA player to a 10-day contract with the option to renew for another 10 days. After that, if the club wants to keep a player it has to sign him for the rest of the season.

Last season, 24 CBA players were called up by NBA teams and two are still there, Quintin Dailey of the Clippers and Craig Ehlo of the Cleveland Cavaliers. Altogether, 39 former CBA players started the 1987-88 season in the NBA.

Success stories like these help the CBA’s reputation. And it has a long one to live down.

It was begun as the Eastern Basketball League in 1942 in Pennsylvania by a group of industrial workers. In 1977, Jim Drucker, who was the league’s lawyer, spearheaded the change to the CBA, then served as commissioner for the first eight years.

“In the beginning the league was literally a day-to-day existence,” Drucker recalled. “I didn’t worry about players showing up for a game in matching socks. I just hoped they would show up.”

For most of the last decade, the CBA has been a ragtag league. Teams really did play in high school gyms and really did spend hours driving from game to game. Ken Drooz, public relations director from 1982 to ’84 for the defunct Detroit Spirits, recalls one of those marathon trips he took with such former NBA players as Marvin Barnes, Kenny Higgs and Terry Deurod.

“We played five games in a row and 11 in 13 days,” he said. “After the fifth game in Detroit, we drove eight hours through the night to Lancaster, Pa., and played a game that same night.

“Then on to Albany, N.Y.--336 miles--for a game the next night. Right after that game we drove to Bangor, Me., to play two more. Back to Rochester for one, then another eight hours back to Lancaster for a game that night. And finally, another eight hours home to Detroit.

“It was a caravan. The coach drove his car, I drove mine and somebody drove the van. It was dark and cold and icy, and we did this for eight days.

“We had one overnight at the Bangor Holiday Inn,” Drooz said. “We asked the desk clerk where a decent night spot was in town. The clerk looked at us and said, ‘This is it.’ That’s when we knew it was going to be a long series.”

That’s exactly the image the CBA is trying to shake nowadays. Although not as colorful, the new stories coming out of the league paint a much brighter picture, likening the CBA to a Triple-A baseball league.

The 52-game season runs for 17 weeks from mid-November to mid-March, with playoffs following. To ensure that players hustle, there is a bonus-point standings system. Teams get a point for each quarter they lead and three points for winning the game.

The league has its headquarters in Denver, a marketing division in Center Square, Pa., and 12 franchised teams, most in the Midwest and on the East Coast. The CBA works closely with the NBA to train referees, develop drug and alcohol rehabilitation programs, and test new equipment or rule changes. The CBA, for instance, is shooting three-pointers from about 18 inches closer as a test for the NBA.

“We provide the CBA’s officiating and a direct cash subsidy,” said NBA Commissioner David Stern. “The measure of success of the CBA players and the entire league results in subsequent opportunities in the NBA. George Karl, now the coach of the Golden State Warriors, coached in the CBA, and our NBA rosters are dotted with former CBA players.

“The CBA has changed in every aspect. It now has better arenas, coaches, travel and exposure, and better pay. It is seen now as a first-class minor league.”

The NBA subsidy is the major reason for the CBA’s rise from rags to riches. Carl Scheer, who took over as CBA commissioner in 1986, negotiated a contract with the NBA that nearly doubled the subsidy to 1.8 million for three years. That money is divided among the 12 teams, and used primarily to improve pay, playing and travel conditions.

Scheer also negotiated a television contract with ESPN--the CBA bought the air time and sold the advertising--that is providing an opportunity for national exposure.

League attendance was up in 1987 by 125,000 and averaged 2,296. Franchises are selling for $450,000, up from $200,000 three years ago.

“I think once we realized who we were, the CBA owners and the league office learned how we could be successful,” Scheer said. “We finally realized we couldn’t compete in the big cities. CBA teams work best in small cities that do not have major basketball programs.”

There is no better example of this then that of the La Crosse Catbirds. Originally, this team was in Louisville. Not surprisingly, considering the success of the University of Louisville’s basketball program, the Catbirds struggled.

So, they moved to La Crosse, a Mississippi River city of about 50,000 and no major sports competition. Now, they average about 5,000 fans a game and broke the league attendance record last year by drawing 122,000 for the season.

Scheer left the CBA recently to join the Charlotte Hornets, one of the NBA’s expansion teams. Mike Storen replaced him Jan. 1.

“Hopefully, now that I am here, I can convince the NBA that it would help the industry to have a more direct minor league system,” Scheer said. “I think it would accelerate the development of players and help to stabilize the system. It would give the player a better financial base and a better opportunity to develop and learn to be comfortable with the parent club.

“Now, it’s a candy store approach. NBA clubs can look in the window and pick and choose who they want, but you are not developing talent that way. It is just a short-term solution.”

Stern disagrees. “As our relationship with the CBA has evolved, we have adopted it as a minor league,” he said. “Direct affiliations with individual clubs would limit the access of NBA teams to CBA players, as well as the access of CBA players to NBA teams.

“We subsidize the league as a whole and, as a result, if any team in the NBA needs a player they can deal directly with the player.”

Of the 161 college draft picks in 1987, only 43 opened the season with NBA teams. The 118 others had two choices if they wanted to continue to play competitive basketball--play in a foreign country or try out for a CBA team.

The lure of money and the glamour of playing in France or Italy is easier on the ego than making $450 a week and playing for a team named the Topeka Sizzlers. But if a player wants to stay visible to NBA scouts, his best chance probably is in the CBA.

Milt Wagner helped lead Louisville to the National Collegiate Athletic Assn. championship in 1986, then found himself playing for the Rockford Lightning that same year.

“It was a real downfall for me to sign with the CBA because I thought I would go straight from Louisville to an NBA team without any detours,” Wagner said.

“I think you have to go there with the mental attitude to improve yourself and play well. That’s what I did and I was invited to a couple of NBA camps that next year.”

Wagner chose the Laker camp and made the team.

“I always heard stories about the CBA that weren’t so good, but it has improved,” he said. “It’s just the fact of being in the CBA that can be a real downfall. One of my teammates at Rockford, Pace Mannion, is now with the (Milwaukee) Bucks, but I think the rest of them are still there.”

Of the 307 players on NBA rosters this season, 253 were first- or second-round draft picks. In contrast, there are many players in the CBA who weren’t even drafted.

CBA players are scouted regularly by NBA clubs as well as by the NBA itself, but the chances of making a team remain slim. Four NBA expansion teams will open some roster spots in the next two seasons, but they will stock their rosters primarily with current NBA players and college draft picks.

Still, hope remains.

Cazzie Russell spent 12 years in the NBA so he knows what it takes to get there. He also knows how important it is to his players to pursue their dream of playing there.

“You don’t have to be an Einstein to figure out these kids want to get to the NBA,” he said. “We don’t have to talk about it. Instead, I work with them individually and try and help perfect their skills.

“If the opportunity knocks, they have to be ready to go. Because you never know if or when the opportunity to play in the NBA will come again.

“It may be just one small thing keeping them from making the NBA, one fundamental skill,” Russell said. “I wonder sometimes if a player is too advanced to take him back and teach him the right way. But I always try.

“All of my players have talent, but sometimes they just may not be NBA material. You never quite know for sure if they won’t make it, but you’ll get an idea.

“It’s a sad type of feeling.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.