The Play of the Eyes<i> by Elias Canetti; translated from the German by Ralph Manheim (Farrar, Straus & Giroux: $22.50; 329 pp.) </i>

This third volume of memoirs by Elias Canetti, 1981 Nobelist in Literature, translated into a comfortable, intelligent English by Ralph Manheim, covers the years 1933-1937, just after the completion of “Kant Catches Fire,” his first and only novel, later called “Auto-da-Fe.” A fascinating work in every detail, “The Play of the Eyes” is not your usual autobiography; indeed, scarcely anything happens in it by way of story, except for two encounters with Canetti’s powerful, soul-devouring mother--one of reconciliation, the other a deathbed watch at the close.

Instead of events, gossip or history, Canetti gives us what most matters ultimately: contemplative, penetrating analyses of famous, even notorious artists, writers, and intellectuals who inhabited the suffocating hothouse of intellectual Vienna in those tumultuous years preceding the disaster of Anschluss . In subtle ways we do not see from latter-day hagiographers who lack the precious, personal knowledge of intimacy, he evokes such as Alma Mahler (whom he loathed), and her daughter Anna (whom he adored), Robert Musil, Hermann Broch, Ernst Bloch, Oscar Kokoschka, Franz Werfel, Fritz Wotruba, Alban Berg, Herman Scherchen and others--names suggesting achievements that remain landmarks today in literature, music and art. During the four or so years covered, Canetti, not yet 30, tells us little about himself and his shocking (at the time) first works of fiction and drama, which he was trying to get published and produced. It would have been foolish and vain to have done so, even if he were not a Nobel laureate, for the works themselves matter, not chitchat about them.

Rather, he takes us along his visits to the people who carried those names and were his friends, distilling his impressions for us until we come to grasp the meaning of what artistic effort in that doomed, perfervid, disastrous Central Europe was about: We perceive an intensely lived intellectual activity quite unknown today, a passion about culture certainly never experienced in America. The most extraordinary portrait of all is that of Sonne, his true mentor, someone no one in the world but Canetti seems to have known then or after. What one would give to have had such a person at the crucial moment of one’s youth, and to have heard him speak as Canetti did: the unacknowledged disciple of an unacknowledged master!

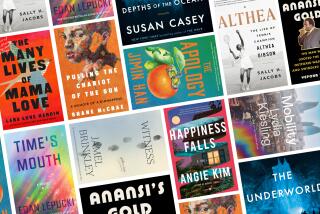

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.