New Management Hopes Changes Will Bring Back Readers, Advertisers : California Business Magazine Starts on Comeback Trail

Karl Fleming, the publisher and editor-in-chief, figures it will take about 17 months to get California Business magazine out of the car leasing business.

By then, he hopes to have a few other knots untangled, too.

When Fleming took over the glossy financial monthly last September, he found that 15 of the Los Angeles magazine’s 33 employees drove leased cars made available to them by the company. He couldn’t break the leases. So he decided to rent the cars out, some to employees and the rest to whoever might want them.

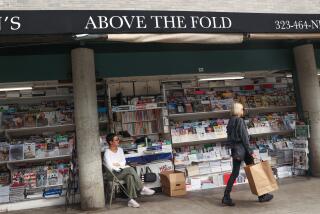

This week, what Fleming hopes will seem an untangled version of the magazine itself will hit newsstands, the first to reflect new management’s refashioning.

Advertisers already are responding, Fleming said, and the magazine will break even in May for the first time in nearly a year.

But it remains to be seen whether subscribers who fled the magazine in the last year will return, or whether Fleming, Editor Bill Blaylock and their new staff will be able to bring to the 20-year-old publication the journalistic and financial respectability that it has always lacked.

Purchased by Stone in 1978

“I want to be able to sit down in public and not be embarrassed to be carrying California Business under my arm,” Blaylock said.

For many years, California Business magazine seemed, as one insider put it, “an excuse for owner Martin Stone to write a column back in his home state.”

Stone, who bought the magazine in 1978 when it was a semi-monthly newspaper, was the outspoken chairman of Monogram Industries in Santa Monica, an airplane toilet manufacturer that he transformed into a multimillion-dollar conglomerate.

Stone and partners sold Monogram in 1982, and he now runs a real estate firm called Adirondack Corp. and lives in Lake Placid, N.Y.

Stone used his magazine column to espouse free-market philosophies and rail against presidential policies. He also had the magazine transformed into a glossy monthly regional periodical.

Journalistically and financially, however, it rarely became more than the “costly avocation” that Stone described it as shortly after the purchase.

“They used photos supplied by tourist bureaus,” Blaylock said.

“I felt the previous staff was doing a solid professional job, but it was a very unexciting product,” Stone countered.

Only One Profitable Year

The magazine was best known for its propensity for ranking things Californian, such as the state’s 75 “hottest stocks” or 500 largest corporations.

Advertisers seemed satisfied. In 1984, for instance, the magazine sold a healthy 1,000 pages of advertising, an average of 83 pages an issue.

Profits, however, proved slim. The magazine made money only once, in 1984, and even that was “marginal,” Stone said.

One problem was keeping readers. California Business had to spend a great deal of money sending out free copies or pushing discounts and promotions to guarantee to advertisers its circulation base of 70,000.

Another problem was overhead. Rent on California Business’ impressive Mid-Wilshire headquarters, Fleming said, is $19,000 a month. Fleming said he thinks that he can rent sufficient space for $7,000, but nearly three years remain on his lease.

And employees enjoyed those free cars and seven weeks of vacation as well.

“I’m the primary person at fault,” said Stone, who has invested $5.5 million in the magazine over eight years. “I wasn’t paying much attention.”

Stone erred again in 1985, he says now, when he decided to sell the magazine once it had turned a profit.

Last June, he struck a deal to sell it for $7.1 million to a Texas business magazine group, Commerce Publishing. In September, the deal collapsed.

Precisely why remains unclear because the two sides tell different versions of what transpired.

Stone said he pulled out because the financing “came through in a distorted fashion,” with him taking a secondary position to Commerce’s lenders in case of default.

However, E. Jack Martin, president of Commerce, said the deal collapsed because “when we more fully examined” the magazine’s financial situation, Commerce discovered “a lot of current and long-term liability that we had not been aware of.”

Martin dropped his bid to “considerably less” than $7.1 million, and the deal fizzled.

If Commerce considered the magazine’s fortunes problematic, they became even worse during the months of sale negotiations. In the final two, Fleming says now, the advertising sales staff had virtually stopped working and advertising linage shriveled. Paid circulation also dropped below the 49,000 level required by the Audit Bureau of Circulations to support total circulation of 70,000.

Stone says he decided under the circumstances to rebuild the magazine rather than attempt another sale of a depleted product.

Fleming, a veteran TV and magazine journalist, had known Stone from the days between 1965 and 1973 when Fleming was Los Angeles bureau chief for Newsweek.

In 1975, Fleming wrote with his wife a book called “The First Time,” an anthology of interviews with celebrities, athletes and authors about losing their virginity.

Fleming also edited a newspaper called LA--a weekly that survived eight months in 1972 in Los Angeles--where he made headlines by publishing a hoax.

Fleming paid $30,000 for the story of a man claiming to be mysterious skyjacker D. B. Cooper, only to discover later that the man was an imposter. Fleming wrote the story anyway, saving until the third weekly installment the fact that the story was a phony and that he had been duped.

At California Business, Fleming has made several changes beyond trying to dispose of his fleet of cars.

First, “I wanted my own team,” he said. Today, only four of the 33 staff members remain at the magazine. Twenty-seven others are new. Among them is Blaylock, a Ph.D. from the London School of Economics who was highly regarded as a Time magazine correspondent in Paris, London, Washington, Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Fleming and Blaylock said they have doubled the rates that they will pay writers for stories--from 25 cents a word to roughly 50 cents--in hopes of attracting more-accomplished reporters.

They also say they have reduced overhead to the point that they can break even with 60 pages of advertising in a 96-page magazine, a level they say they have reached in the May issue. Previously, Fleming said, the magazine needed 67 pages of advertising to break even for every 100 pages.

Natural Market

Fleming also maintains that the magazine has a natural market niche. Although the magazine must must compete for readers and advertising with such publications as Inc. magazine, Venture, Entrepreneur, Savvy and Money, he argues that California is a natural market all its own. And only Money, with a circulation of 90,000 in the state, has more readers here.

But what has proven most elusive is a product that holds readers. Fleming hopes to change that by orienting the magazine more around people in business. Business, Fleming said, “is drama, it’s buccaneers and adventurers and pioneers and heroes and villains.”

Blaylock said he hopes to improve the magazine’s writing, graphics and the scope of coverage.

Stories in the April issue are shorter and include a wider variety of topics, including a feature for executives on changing drinking habits and whether nepotism is good or bad business.

The April issue a year ago stuck to more traditional subjects: real estate, taxes, corporate strategies, financial planning, marketing and small business.

Some may find Fleming’s approach glitzy. He is planning “Gold Nugget Awards” to be given to the best in categories such as business person, sales person or new executive. And the May cover will feature former body builder Arnold Schwarzenegger in a business suit.

“Some conservatives may ask why we’re putting him on the cover,” Fleming admitted, “but it’s not a story about his wedding party with Maria Shriver.”

Stone agreed. “April is good. May is going to be even better.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.