Commodore International declared itself insolvent on April 29, 1994 under Chapter 7 of US bankruptcy law. Ordinarily, this would have been followed immediately by an auction of all the company’s assets. However, Commodore’s Byzantine organizational structure—designed to serve as a tax shelter for financier Irving Gould—made this process far more lengthy and complicated than it should have been.

During this time, Commodore UK, Ltd. continued to operate. It had been the strongest of all the subsidiary companies, and it always had a positive cash flow. As the other subsidiaries went under, Commodore UK purchased all of their remaining inventory and continued to sell Amigas to British customers.

The head of Commodore UK, David Pleasance, hatched a plan to purchase the mother company’s assets at auction. His idea was to raise enough money not only to buy Commodore International but to fund the new company as an ongoing concern, including the continuation of research and development projects. The business plan was to continue to sell Amiga 1200 and 4000 computers and CD32 consoles while slowly transitioning to next-generation hardware based on Dave Haynie’s Hombre RISC architecture.

Pleasance raised about $15 million from local investors, which was enough to win the auction. For the rest of the money, he arranged a deal with a curious partner: New Star Electronics, based out of China.

New Star got its start by selling unlicensed clones of the Super Nintendo and Sega Genesis consoles—the clones not only played the same games, but they looked identical to their legitimate counterparts. Under pressure from the Chinese government, New Star had decided to change its business model, and it was looking for game companies willing to license their devices. David Pleasance arranged a deal worth $25 million for New Star to produce and sell Amigas for the Asian market.

Other companies were also vying for Commodore International’s assets. Dell Computer put in a $15 million bid—but it was late. The bankruptcy judge refused to wait for Dell to do its due diligence. Six months had already passed, and the only remaining contender in the race was a European PC manufacturer named Escom, which put in a bid of $14 million. Originally Escom wanted to bid only on the Commodore brand, but the company raised its stake to all the Commodore assets after other bidders complained.

With only thirty-six hours to go before the end of the auction, New Star told Commodore UK that it was backing out of the deal. Without enough money to guarantee the continuation of the business, David Pleasance withdrew his bid. All of a sudden, Escom was the new owner of Commodore and the Amiga.

Enter Escom

Schmitt’s company had been saved in its infancy when he was able to secure a large purchase of Commodore 64s for the Christmas 1991 season. He did so by making a personal phone call to Commodore’s global logistics director, a man named Petro Tyschtschenko. During the bankruptcy negotiations, Schmitt called Petro again to get help with the process. After Escom won the auction for Commodore’s assets, Schmitt split the company into two subsidiaries: Commodore BV in Holland (which became the holder of the Commodore trademark) and Amiga Technologies, whose name was self-explanatory. Schmitt rewarded Petro with a new job as the director of Amiga Technologies.

At first, this wasn’t much of a job. Escom had only been interested in the Commodore name, and putting all the Amiga assets together in a single division seemed like a prelude to selling them off. However, Escom was soon buried under a deluge of mail and phone calls from Amiga owners and fans, pleading with the company to keep their beloved computer alive.

Petro was keen on keeping the flame going, as he had been a fan of the Amiga back in his Commodore days. However, the task wasn’t going to be easy. In the wake of Commodore’s demise, factories around the world had been sold, and parts suppliers moved on. Just restarting production of Amiga 1200s and Amiga 4000s required building a brand new factory in Scotland, which wasn’t able to deliver machines until October 1995. By then, it was a year and a half since Commodore had declared bankruptcy.

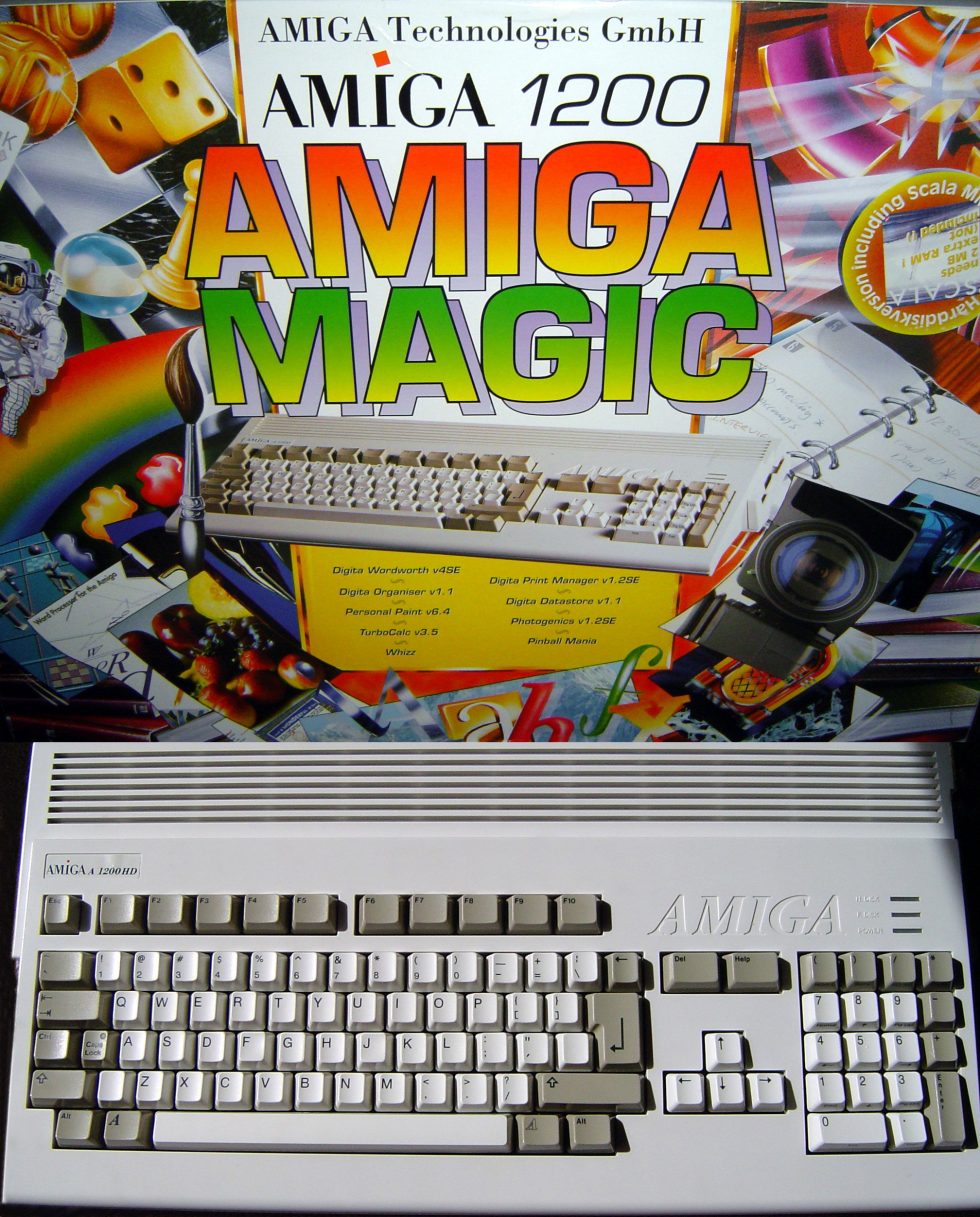

Still, Amiga Technologies soldiered on. The subsidiary company revealed a new Amiga logo and released a hardware and software bundle called the Amiga Magic Pack. This was an Amiga 1200, sold for £400 in a single box, along with two games, the Deluxe Paint AGA painting software, the Wordsworth 2 word processor, and Print Manager. A £500 bundle was released that added a hard drive and more productivity software. These Magic Packs were reasonably good deals, albeit saddled with aging computer hardware. Sales were poor in England but a little better in Germany, where Escom had greater marketing presence.

In Asia, Amiga Technologies licensed its hardware, not to New Star as everybody had expected, but to another Chinese company called Regent Electronics Corporation. With the help of ex-Commodore engineers, Regent designed and built a set-top box called the Wonder TV A6000, which was eventually released to a small set of Shanghai residents in 1997.

reader comments

164