Mystery solved: Where was the wreck of Dana Point’s wind-bashed bait boat?

Nearly two years after Dana Point’s bait hauler went down in wind-whipped waters off the coast of San Clemente, Chad Steffen was taking a group of anglers out on the San Mateo, one of several boats in Dana Wharf’s Sportfishing fleet. It was June 2007.

“During the summer, we’ll head down the coast for a day trip and fish the typical spots,” Steffen explained. “As a fleet, we’re going to swing to the outside a little bit, to a depth range of 90 to 240 feet. Sometimes we’ll stagger ourselves as we’re looking for fish coming up from Baja.”

As captain, Steffen watched his Fathometer, an echo sounder used for measuring the depth of water, closely as the San Mateo motored a few miles out of the harbor.

“We ran over an edge of something where there was a solid indication of fish,” he said. “I turned the boat around and came back to try to find it again, and the second time I was thinking, ‘What the heck is this?’ Considering the time of year, I was also thinking it could be a really concentrated ball of sand bass. We anchored on it and immediately started catching sand bass, but then we started catching rockfish too, which are structure fish — you’re not going to find them out in the mud.

“I’ve been fishing these areas for several years, and I knew there was no structure down there so it had to be something new. That’s when I thought it was probably the A.C.E. and wrote the coordinates down.”

Early on Nov. 26, 2005, the A.C.E., a 58-foot drum seiner, was en route to the Dana Point Harbor after a night of bait fishing. Offshore winds, which kicked up a sharp and quick chop producing vertically shaped waves breaking only seconds apart, slammed the boat relentlessly until it finally capsized. The vessel had already been listing from a leaking deck hatch.

Because it flipped so quickly, the crew was unable to grab any life jackets. The emergency radio beacon failed to send a signal to the Coast Guard, and the life raft failed to automatically inflate.

Amazingly, the captain, Robert Machado, and three crew members survived without serious injury and were able to swim to the 14-foot skiff the A.C.E. was towing and shoot off emergency flares. San Clemente resident Ed Westberg spotted the red sparks from his ocean-view home around 3 a.m. and called the Harbor Patrol. With Westberg’s help, the two deputies located the skiff before it was dragged under. Accounts of the dramatic rescue were widely published.

For weeks after the accident, the Orange County Sheriff’s Department’s underwater search and recovery team, the Coast Guard, fishermen and virtually anybody with a boat and sonar device went searching for the A.C.E. but came up empty.

Now Steffen thought he might be on it.

“When I realized it was most likely the A.C.E., I wanted to keep that to myself — I didn’t want the word to get out,” he said, his interest in the prospect of a great haul overriding the fact that he may have solved a puzzle. “The other boats in the fleet weren’t catching anything, so they moved to other spots and I didn’t tell them we were catching rockfish either. We stayed on it for a couple of hours and caught a lot of fish.”

The only time he went back was when the fishing was really slow at the other spots or when there were no other boats that would see him there or a combination of the two scenarios. “I didn’t want to hammer it all the time,” he said.

Like good poker players, Steffen and his deck hand, Josh Aardema, kept quiet for a solid year. Eventually word got out and people grew more curious.

“We’re a pretty close-knit community here,” Steffen said. “There were people who were actually mad at me for not telling them where it was. We share information about fishing spots all the time, but this one was mine, and I wasn’t giving it to anybody.”

Even though word leaked about the boat’s location, no one else had found it.

“Then people started looking a lot harder — they knew the general area of where it went down — but it’s a big area,” Steffen recounted. “You get out of the harbor and you don’t realize how much ocean there is to cover. Nobody knew which way the A.C.E. was drifting when it sank.”

About a year after Steffen marked the site, Roger Healy, a local diver and fisherman, expressed interest in diving it. Healy contacted Ken Nielsen, who owns and operates the Early Bird II, and together with Bob Lohrman they waited for the right weather conditions.

“Roger said he wanted to dive the site and he wouldn’t share the location with anyone else,” said Steffen. “He was the only one I gave the numbers to. While I was reluctant to give them out, I was also curious.”

While Steffen is credited with finding the wreck, Healy and Lohrman were the first to dive on it.

“We used sonar to locate it and anchored on it,” said Nielsen. “Healy and Lohrman put on their dive gear and went down to see if we were, in fact, on the boat. A few minutes later, I’m sitting on the deck and all of a sudden the life ring pops up right by the side of the boat.”

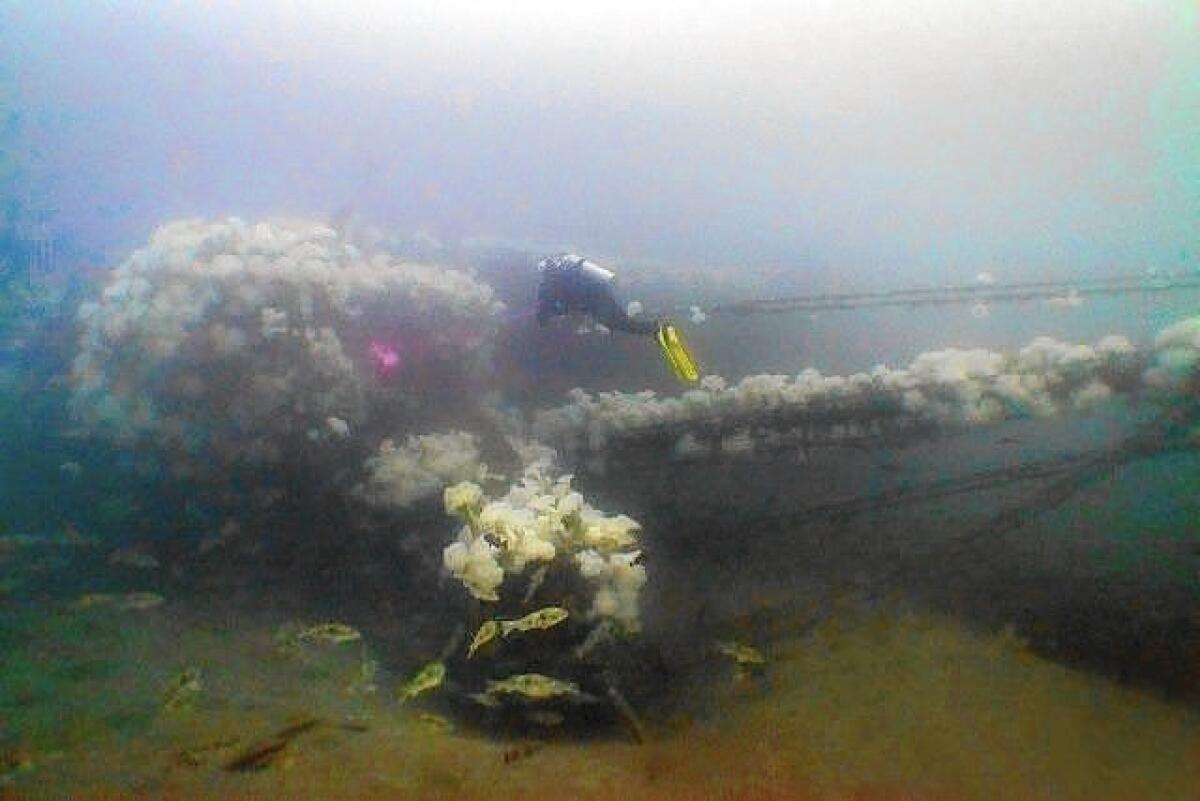

Recalls Healy: “The first thing I saw was the life ring and swam right to it and cut it off. We wanted to establish that it was the A.C.E. It was eerie … especially being the first ones to dive on it. Thank God no one died when it sank. I swam inside the wheelhouse and I thought, ‘What am I doing in here? I don’t have much bottom time. Who knows what could snag me.’

“We took a loop around the boat, and I had my camera and we went up to the bow. We scraped the bow until we could see the name, and we took a couple of pictures just like anybody would do diving a shipwreck. The skiff was still attached to the stern, and the drum net still had burlap covering it — it was in perfect condition.”

As a gesture of goodwill, they returned the A.C.E.’s life ring to Buck Everingham, who owned the boat. It was named after Buck’s grandfather Adolphus Charles Everingham, who launched Everingham Bros. Bait Co. in the 1950s.

By 2010, Steffen’s closely guarded fishing spot had become a heavily trafficked area for anglers and divers. For the local dive shop, the wreck was a boon for business, considering its close proximity to the harbor and because of the newly launched charter the Riviera, a dive vessel. So familiar had the site become that several buoys, set to help boat captains locate it easily, were cut. And because it’s a popular fishing spot, fishermen didn’t want to risk having their fishing lines get wrapped around a buoy, thus threatening their catch.

Another issue was depth. At 114 feet, reaching the wreck requires advanced diver skills, and some feared that if the site was buoyed, people would be tempted to see it firsthand and accidents would occur. One diving fatality has already been recorded.

Some people see the wreck as a sacred part of Dana Point’s fishing history and hope it is never disturbed.

“You can understand the frustration,” Healy said. “There was a very small group of people who knew about it for a fairly long time. And there aren’t a lot of unique areas left like that.”

*

Marshutz is a freelance writer based in Dana Point.