Apodaca: Compulsory national service is a long shot, but let’s talk about the idea

I recently had the privilege of attending a speech by the renowned presidential historian Doris Kearns Goodwin. She has long been a hero of mine, and I had been eager to hear her thoughts on the topic of her latest book, “Leadership in Turbulent Times.”

She delivered a riveting speech, full of wit, wisdom and illuminating anecdotes. Yet after her formal address was complete, it was her answer to a question from an audience member that particularly caught my attention.

When asked something to the effect of what she would change if she could, Goodwin replied that she is very interested in the concept of compulsory national service.

It’s an intriguing idea that has been around since at least the 1800s, although it has always failed to gain much traction.

Attempts to revive the concept have come from both ends of the political spectrum, yet those efforts have consistently failed and polls have shown that the public remains stubbornly ambivalent about the idea. As recently as 2003 to 2013, former U.S. Rep. Charles Rangel (D-NY) made five unsuccessful attempts to pass a Universal National Service Act, which would have required all people in the United States between the ages of 18 and 42 to either serve in the military or perform civilian service related to national defense.

Still, it’s worth keeping the discussion about national service in the mix, at a minimum as a thought experiment into what benefits might accrue if we ever decided to take the plunge.

When we think of mandatory national service, it’s generally in connection with military service. Indeed, about 85 countries have some form of obligatory military service. In the U.S. we maintain the requirement that all males ages 18 to 25 must register with the Selective Service, meaning they would be obligated to serve in the military if a draft is ever reinstated.

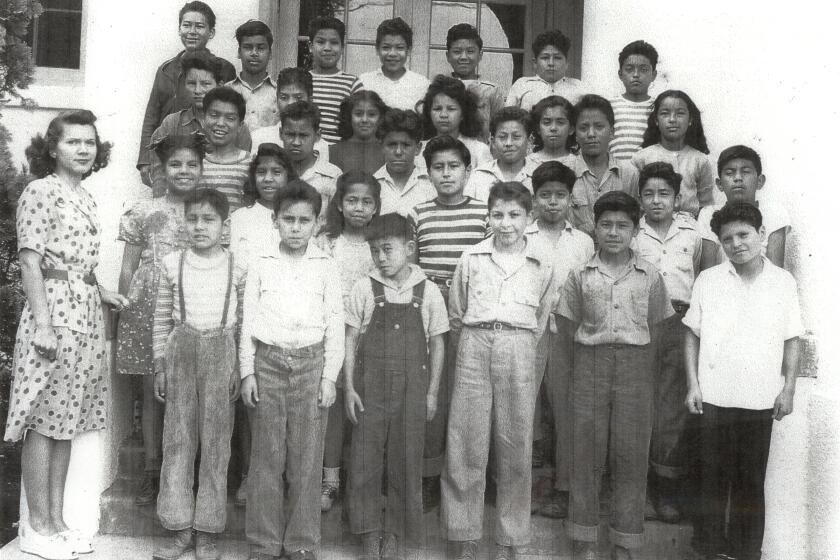

Columnist Patrice Apodaca remembers Mendez, et al vs. Westminster, in which the court held that separate “Mexican schools” were unconstitutional.

But some proposals have sought a broader mandate that would include work on civilian projects such as teaching in low-income areas, helping care for the elderly, providing healthcare to hard-to-reach communities, or repairing and maintaining infrastructure.

Proponents of the idea cite several potential benefits, including the opportunity to promote national unity by bringing people of diverse backgrounds together in a shared purpose for the betterment of the country. They also argue that it would be a cost-effective means of providing critical support for programs that improve educational outcomes, reduce poverty and lower crime rates.

Young people who fulfilled their national service requirement — by, say, devoting one or two years after high school or college to working in needy communities — would gain maturity, real-world experience, compassion and practical skills, advocates believe.

To be sure, there are plenty of arguments against compulsory service, not the least of which is that in this country we generally don’t conform easily to national mandates of any kind, often seeing them as an infringement on personal liberty. If that hadn’t been obvious before the pandemic, it’s certainly crystal clear now. Americans don’t like being told what to do, even when an order promotes the common good.

Many among us are of the opinion that it’s best to leave service initiatives to charitable organizations and voluntary government-funded programs such as AmeriCorps, Teach for America and the Peace Corps.

A mandatory service program would also be ripe for manipulation and exploitation, critics argue. (See: college admissions, workplaces or pretty much any institution that’s riddled with inequality and favoritism.) There would surely be legal challenges aplenty.

Some people might also be scared off because of a perception that service workers could be exposed to some dicey circumstances. They might cite the example of Mexico, which has long required medical students to fulfill a year of community service as a means of improving healthcare in isolated communities. Last month one such student was shot to death inside the hospital where he worked in rural Durango state, and others have spoken up about the dangers and violence they sometimes encounter while serving.

I’m not suggesting that an experiment of our own into mandatory national service would be problem-free, or that complicating factors would not arise. Certainly a lot of study, negotiation and sustained effort by policy makers would be required to craft a program that is creative, flexible, fair (or at least fair-ish), effective and, of course, as safe as possible. We could start gradually, perhaps with a task force that would propose various models aimed at some of our most pressing issues — homelessness, climate change or crumbling infrastructure, for starters.

Such an initiative might actually be a rare opportunity for bipartisan cooperation and — dare I suggest it? — compromise.

As I mentioned, it’s a long shot. We’ve become unaccustomed to taking big policy risks, and we spend a lot more time talking about what’s wrong and who’s to blame than trying to craft bold, inventive solutions.

Call me an idealist — that’s almost a pejorative these days — but if at least we could agree that mandatory national service is an interesting idea that’s worthy of discussion, then maybe, who knows? We might take a small but meaningful step toward working together again. Imagine that.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.