Losing ‘Sunny,’ Part 1: Two decades after a young woman’s brutal slaying, those left behind still try to cope

Richard Johnson was angry.

But he tried to turn his anger over what happened to his girlfriend into something that would help keep her memory alive.

In May 1997, less than three months after she died, Johnson opened AAA Electra 99 in a small space on 30th Street on the Balboa Peninsula in Newport Beach. The art gallery’s name combined AAA — a trick from his work for cab companies to secure one of the first spots in the phone book — with Electra 99, a phrase his girlfriend used to copyright her photography.

Its motto was “Any art accepted,” and it kept its promise, displaying works from the conventional to the grotesque. There were no framed pieces in neat rows on sanitized white walls. Instead, artwork covered every surface. Cigarette smoke filled the gallery when bands played all-ages shows.

Johnson and his girlfriend, Adrienne “Sunny” Sudweeks, had often discussed opening a gallery that would welcome unconventional art and artists — people whose work had been shunned at coffee shops and mainstream galleries. Johnson considered it a pipe dream, but after Adrienne died he felt compelled to make it work.

Of all the goals they had — including marriage and children — he could accomplish this one alone.

The gallery could be her legacy. People might remember her for that instead of as the victim of a brutal slaying that would go unsolved for two decades.

And maybe it could help him get over the cloud of suspicion he faced about whether he was involved.

Johnson moved the gallery across town after neighbors on the peninsula complained, and then moved it to a warehouse in Anaheim, where it remained until it closed in 2012.

“I’m quite proud of Electra because I think that’s how Adrienne is remembered,” he said. “She has a semi-legacy in the form of things that came out of the gallery that still go on. I’d like that to be her legacy, not the rest of this.”

Nevertheless, Johnson muses about whether AAA Electra 99 would have been more successful had Adrienne lived.

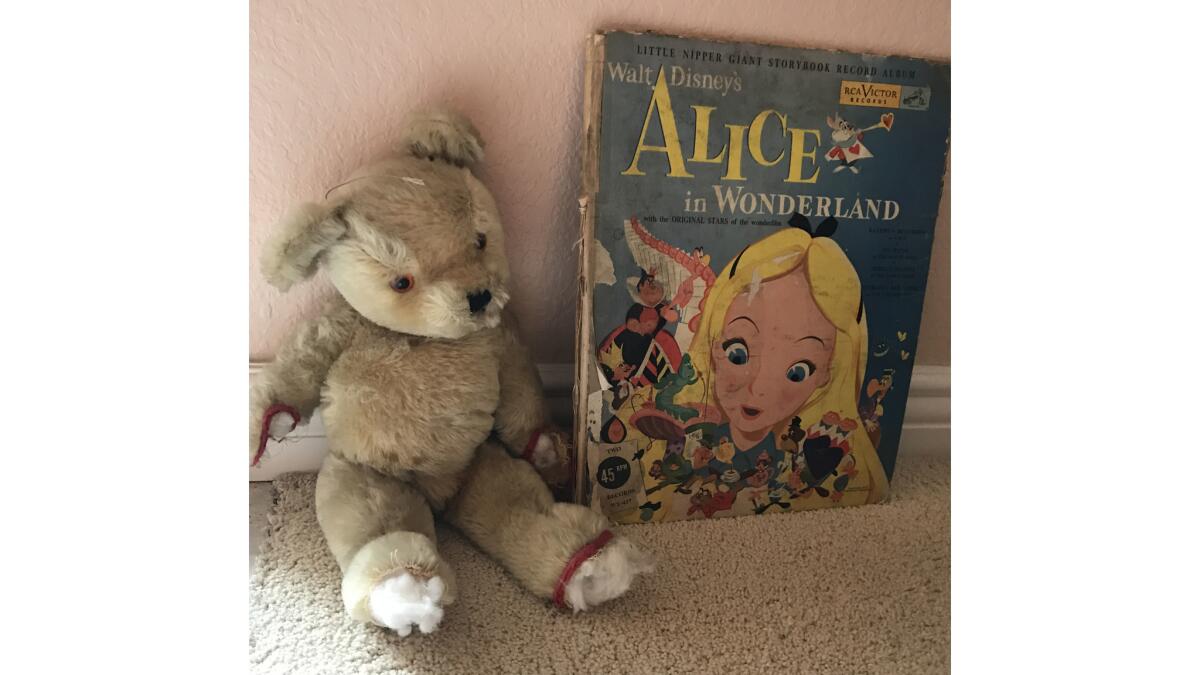

A worn tan teddy bear — cloud-like stuffing spilling from its arms and legs — sits beside a tattered hardback copy of “Alice in Wonderland” against a living room wall in Sandy Sudweeks’ three-bedroom house in Costa Mesa’s Westside.

The literary artifact is from Sandy’s childhood, representing an openness to new and sometimes strange experiences — a trait instilled in her at age 5 when she saw Disney’s screen interpretation of Lewis Carroll’s classic with her father.

It’s a trait her daughter, Adrienne, inherited.

The teddy bear was Adrienne’s, a childhood gift from her grandmother. The display — prominently positioned for decades on the plush beige carpet beside the sliding glass door — invites questions. It’s a window into a mother’s worst fear — losing a child in a senseless crime.

At 73, Sandy recently retired from teaching communications at Golden West College in Huntington Beach. Her wit and warm smile draw people to her.

Though she has been divorced from Adrienne’s father, Alan Sudweeks, since before their daughter’s death, they remain close. Alan, a retired physician, lives in Arizona, but the two often travel together with their grandchildren.

Sandy, a student of Buddhism since her early 20s, has a worldly essence, and despite the pain she has endured, she says she doesn’t dwell on it, preferring to see and experience as much of life’s beauty as she can.

Her 26-year-old daughter, after all, was robbed of that opportunity when she was raped and strangled to death in her Costa Mesa apartment nearly 21 years ago.

Adrienne, a photographer, studied at Orange Coast College in Costa Mesa and worked part time at a local framing and art shop. She wore retro outfits with a mix of couture items and pieces plucked from thrift shops. She loved red shoes.

Behind her horned-rimmed glasses were dazzling green eyes that had a flash of wildness and a keen artist’s flare. She had champagne blond hair and a beaming grin, belying her boldness and sardonic wit.

Friends remember her as kind and funny, always the life of the party.

She wasn’t easily discouraged — not from rocking out at punk shows in Arizona, where she lived before moving to Costa Mesa, nor from being silly. She spoke her mind.

She dreamed of transferring from OCC to art school to study photography.

She wrote poems to inspire herself: You just be beautiful. And be yourself. And be sure of it.

Johnson met her in 1996. He was in the middle of his night shift as a cab driver when an altercation led him to pepper-spray a group of businessmen in his cab. Frustrated, he stopped for a drink at the Stag Bar, a watering hole on the Balboa Peninsula.

Adrienne was there with friends.

The tavern, now called the Stag Bar + Kitchen, was one of Adrienne’s haunts. She impressed friends by opening beer bottles with her teeth. She refused to stand in the winding line for the women’s restroom. She would use the men’s instead.

She and Johnson found themselves standing next to each other at the mahogany bar. She was a little tipsy, Johnson recalled, and seemed to like him right away. Conversation flowed. They bonded over art and music.

He mentioned that he was interested in a different woman, but Adrienne brushed off the notion.

“I’m much better than she is, and I like you, so you shouldn’t worry about that other girl,” she said.

Her bluntness was invigorating.

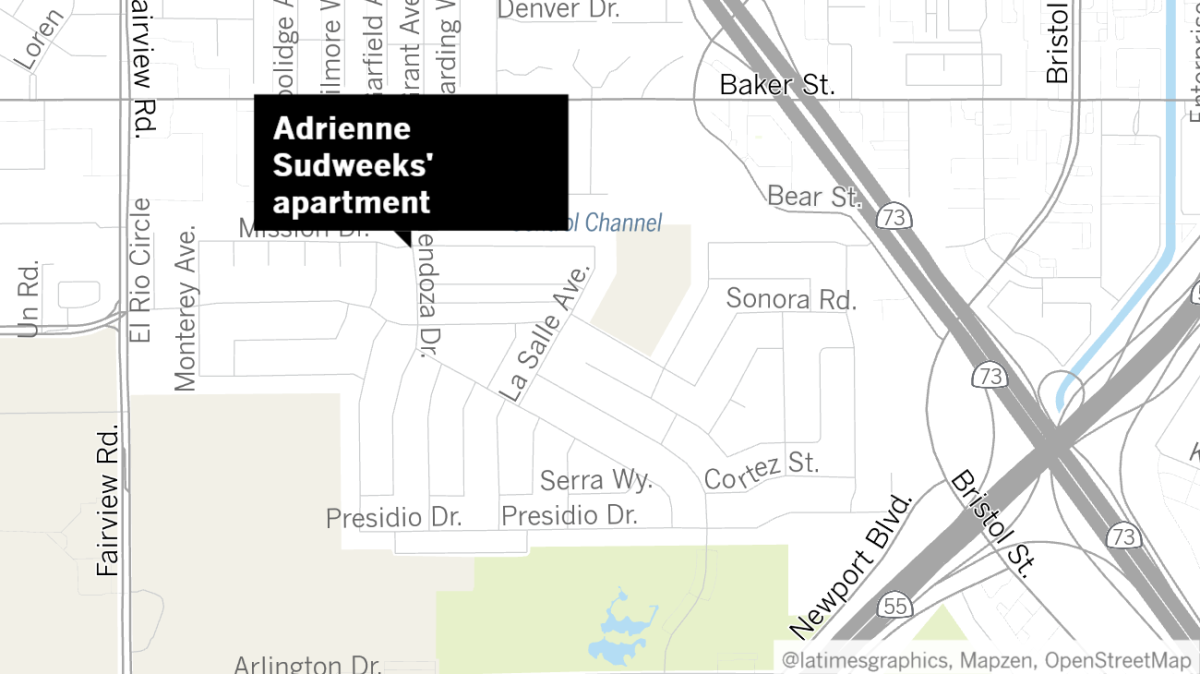

Within a month, Johnson had moved out of his apartment in Huntington Beach and into the three-bedroom apartment on Mission Drive in Costa Mesa that Adrienne shared with another roommate.

In the late ’90s, the area where Mission and Mendoza drives converge was a sketchy pocket. Gangs congregated, drug dealers peddled in alleyways and visitors were reminded to take valuables inside and lock their cars.

In September 1996, Adrienne’s two cameras and flash, lens and camera bag were stolen from her apartment while she slept. The door had been left unlocked after a party.

Afterward, she and Johnson decided to move. A few months later, they found a three-bedroom condominium across town on Pacific Avenue and planned to move in the following March 1.

Three days before her death, Adrienne wrote a letter to a local newspaper, imploring officials not to ignore the Mission Drive area:

“I’m able to move, but why can’t the police or community do anything to help those who can’t? If these problems are ignored now, they will become worse, degrading the city of Costa Mesa.

“Don’t ignore this!!”

On Saturday, Feb. 22, 1997, Adrienne’s black 1967 Volvo was in the garage, broken down, so her mother gave her a ride to Aaron Bros. Art & Framing on 17th Street, where Adrienne worked, and agreed to pick her up after her early-evening shift.

The two discussed an upcoming doctor visit to test Adrienne for attention deficit disorder, which runs in the family. They made plans to look at a more reliable car that her dad offered to help buy.

Friends had invited Adrienne to grab a few drinks at the Stag Bar after her shift, but she opted to stay home and continue packing for the move.

At about 8:30 p.m., a female friend stopped by to pick up some computer cables. The friend, whose name is redacted in police records, drove Adrienne to the Stater Bros. supermarket down the street for groceries and then dropped her off back home.

Johnson sat in his cab outside the Shark Club on Baker Street in Costa Mesa, waiting to be dispatched to a call. He had a few minutes of calm before the Saturday night rush. The dashboard clock read 10:20 p.m.

His cellphone rang. It was Adrienne. They chatted about work and her plans for the night.

She asked him to come home and help her pack.

“I don’t know, honey, we are going to need the money for the new house,” he said.

A dispatcher interrupted, calling Johnson’s cab number over the CB.

“625, where are you?”

The dispatcher directed him to the Huddle, a bar just down Baker.

Johnson told Adrienne about the call. As they were about to hang up, she stopped him.

“I love you,” she said.

His response was quick.

“I love you too, silly. Bye.”

Johnson hurried to the Huddle, took a passenger to Newport Beach and continued his shift.

It was a typical night for an Orange County cab driver. He collected people heading home from bars. He drove a bride and groom from their wedding reception at Margaritaville on West Coast Highway to the Newport Beach Marriott. The wedding photographer snapped a picture of the bride in her white gown, stuffing herself into the back of the cab.

In the apartment on Mission Drive, Adrienne called a few friends before going to sleep. The front door was unlocked, a window left open.

Sometime early the next morning, police believe, a man entered the apartment, found her in bed and raped and strangled her before fleeing.

Johnson returned to the apartment about 3:30 a.m. Feb. 23.

He microwaved leftover mushroom chicken and flipped on an episode of “Star Trek.” His and Adrienne’s roommate, a cabbie named Mike Walterhouse, walked in from an overnight shift and he and Johnson chatted about their fares — who tipped well, who was drunk, where they drove.

Walterhouse, who had a fare to Los Angeles International Airport at 5 a.m., stepped into the bathroom to shower. He yelled out to Johnson that a painting that had been leaning against the wall in the hallway had fallen over.

Johnson figured Adrienne, who had never been a fan of the piece, had knocked into it. He walked into their bedroom, prepared to give her a hard time about it if she woke up.

He shut the door and began to get ready for bed. The room was dark, but light from the hallway peeked under the door, illuminating the bed.

Adrienne was lying at the foot of the mattress under a white sheet.

As soon as he touched her arm he knew something was wrong. She didn’t move. Fear sucked the air from his lungs. He flipped on the light and pulled off the sheet.

She was unconscious and badly beaten. Bruises had formed on her neck. Blood trickled from the side of her mouth.

Johnson ran down the hall and pounded on the door of the bathroom where Walterhouse was showering. Walterhouse, still covered with soap, emerged with a towel around his waist. He looked at Adrienne and began screaming.

Johnson grabbed the phone off the nightstand and called 911. The dispatcher walked Johnson through an attempt to resuscitate Adrienne.

Johnson stared into his girlfiend’s still eyes. He knew — she was gone.

As the blare of sirens heading up the street filled the apartment, Johnson stood, looking at Adrienne. His mind raced.

How could anyone do this?

He stepped backward until his back was against the wall. He slid until he was sitting.

Police ascended the stairs. Officers separated Walterhouse and Johnson on two couches in the living room.

Johnson, suddenly sick to his stomach, vomited. He leaned back on the couch and closed his eyes.

This is the first of four parts. In Part 2, Sandy Sudweeks learns her daughter has been killed, and police set out to find who did it.

Twitter: @HannahFryTCN

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.