Requiem for a riot: Secret files detail deadly police shooting that led to Anaheim protests

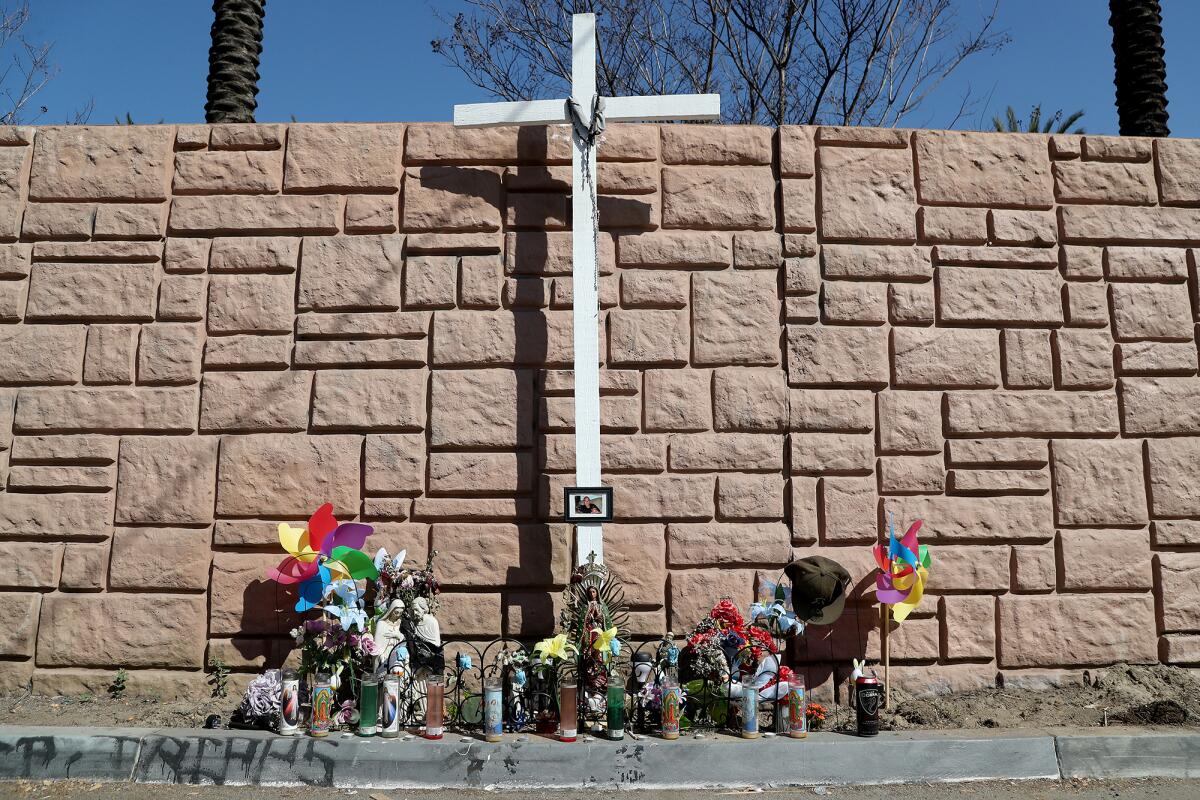

A white cross stands above the wall near where Martin Angel Hernandez died in an Anaheim alley a decade ago. Votive candles and a Virgen de Guadalupe statue are perched on the curb in remembrance.

Gone is the cinderblock wall lined with barbed-wire that overshadowed where the police shooting happened.

A series of palm trees now towers over a beige bulwark that separates the Latino working-class neighborhood under gang injunction from the East Gene Autry Way Extension Bridge, a thoroughfare that connects the Anaheim Resort to the Platinum Triangle.

It also served as an early fault line for downtown riots that erupted over police shootings in the summer of 2012.

Hundreds protested the Hernandez shooting believing he surrendered and was unarmed when felled.

The Orange County district attorney’s office cleared Anaheim policeman Dan Hurtado in January 2013 with a report that states there was “substantial evidence the officer acted reasonably under the circumstances.”

But the legal conclusion did little to mend mistrust among protesters.

As the report details, Hurtado and two other officers responded to a call on the night of March 6, 2012 about five or six suspected gang members gathered in the alley around a white car. The caller reported seeing two handguns, including one placed behind the driver’s seat.

The officers discussed how best to approach the scene over radio. Hurtado took the west side by Haster Street armed with a Bushmaster AR-15 semiautomatic assault rifle; Officers Ray Drabek and Michael Brannigan approached from the east entrance.

As Hurtado crept around the corner, he locked eyes with a woman next to her SUV parked in the alley.

Soon after, Hernandez, a 21-year-old documented gang member known as “Tripps,” ran toward Hurtado’s position flanked by another person on bike. The officer originally planned to stay out of the alley to avoid entering a “crossfire” situation but later told a D.A. investigator that plans changed when he spotted Hernandez holding a shotgun parallel to the ground.

Fearing a carjacking or hostage scenario, Hurtado said that he entered the alley without cover.

The woman caught a glimpse of two people darting down the alley away from others but didn’t see a gun before hiding behind the hood of her car.

Hurtado pointed his rifle at Hernandez, who stopped 20 yards away, turned and ran in the opposite direction. The bicyclist continued peddling past the officer.

“Stop! Put your hands up or I’ll shoot,” the woman overheard Hurtado shout.

Three gun shots rang out soon after. When Hurtado radioed for backup, the woman reemerged and saw Hernandez’s body lying near the wall.

Ten years later, previously secret case files about the shooting are now public record under state Senate Bill 1421, a police transparency law since 2019.

With the Anaheim Riots anniversary nearing, 1,129 documents revealed how the D.A. came to its legal conclusion.

Special assignments

In public D.A. reports, the agency tasked with investigating police shootings for almost all police departments in O.C. touts an “independent and thorough” methodology backed by an “impartial review” of the evidence.

“The investigators assigned to respond to an incident perform a variety of investigative functions that include witness interviews, neighborhood canvass, crime scene processing and evidence collection,” reads the 2013 D.A. report on Hernandez.

What isn’t mentioned was how the agency’s Special Assignment Unit worked closely with Anaheim police on such tasks.

Shortly after midnight, D.A. investigator Katherine Kriskovic, a former Long Beach Police Department detective, responded to the grisly scene where a deceased Hernandez remained in the alley. She became lead investigator and was paired with Anaheim P.D. homicide Det. Karen Schroepfer. Five other detectives worked with the D.A. unit for scene, witness interview and canvassing assignments.

One detective, Bruce Linn, remained under active D.A. investigation for the Aug. 16, 2011 fatal shooting of David Raya, an unarmed Anaheim gang member, when paired to work the scene of Hernandez’s slaying; the D.A. later deemed Linn’s shooting justified in October 2012, just as it had with him in the Caesar Cruz case, another unarmed man shot dead by five Anaheim P.D. officers in 2009.

Anaheim police also accompanied county investigators on neighborhood canvassing and provided Spanish translation for them as needed. When Kriskovic interviewed the key alley witness, Schroepfer was present. The detective joined with Kriskovic again when Hurtado provided voluntary statements in response to their questions two days after the shooting.

Detectives also attended the autopsy which assigned Hernandez’s cause of death as “avulsion of brain” from a through-and-through gunshot to the head.

The D.A. report from 2013 doesn’t mention the bullet’s trajectory.

According to county coroner records, the forensic pathologist “was unable to determine an entrance or exit wound due to the extensive damage to Hernandez’s skull.”

Opposing accounts

A bereaved Caroline Toneygay wanted to know what happened to her son that night.

“I’m hearing that when he got shot by police the first time that he was calling out for help,” she told Schroepfer by phone. “When he stopped in the alley, he said ‘discúlpame, you guys got me.’ He was putting the shotgun down when he got shot in the head.”

The detective cautioned Toneygay against rumor mills but also stressed that if such witnesses existed, they needed to be interviewed by Kriskovic right away.

Schroepfer documented another competing version in a June report.

“Rumor began to circulate that a witness said Hernandez had been shot in the leg, and while pleading for his life, shot in the back of his head,” she wrote. “APD attempted to find this witness. As of this date, this witness has not contacted law enforcement.”

D.A. investigators similarly didn’t find anyone.

When interviewed by Kriskovic, Hurtado said he believed Hernandez ran toward a blue dumpster in the alley to scale over the wall. But then, he turned toward him with the shotgun and “flipped it around the front of his body and was starting to raise the firearm.”

That’s when Hurtado fired three times, striking Hernandez once in the head.

“I got a suspect down,” Hurtado radioed. “He’s got a shotgun that’s down near him.”

A post-riot reform, Anaheim police officers weren’t equipped with body cameras in 2012, but they did wear audio recorders.

“[Didn’t] have one on the evening of the shooting incident?” Kriskovic asked.

“No,” the officer responded.

Hurtado also said his patrol car, which was parked away from the alley, didn’t have any video recording equipment, either.

But cameras were mounted elsewhere with the construction of the $66-million East Gene Autry Way Bridge Extension.

D.A. investigator Rick Bradley, a former Newport Beach policeman, documented two cameras mounted on a pole facing the alley from Haster Street in his scene report. Schroepfer noted a security camera at the same location and that Linn “obtained a copy of the surveillance video.”

Det. Chris Masilon also obtained cellphone footage from a resident with permission.

“All disc recordings and copies were in original form and given to Inv. Kriskovic,” Schroepfer wrote.

From an elevated position, the cellphone video shows Hernandez‘s body after the shooting.

Five OxBlue construction camera photographs provide a wide view of the alley; in D.A. documents, investigators offered no analysis of them.

Even though no witnesses came forward about Hernandez’s being unarmed, Kriskovic contacted the Orange County Crime Laboratory in April to address the allegation.

“She is interested in information to confirm or refute opposing stories presented by officers and media/friends of [the] victim,” reads an unnamed summary of the phone call.

The O.C. Crime Lab, a division of the county’s Sheriff-Coroner Department, took part in the initial investigation at the scene.

“There was apparent blood and tissue on the shotgun,” reads a forensic scientist’s report.

After Kriskovic’s call, another forensic scientist observed the shotgun. He interpreted the bloodstain patterns in a key way: the source was close in range, no more than 19 inches from the muzzle if the shotgun was held upright and horizontal.

The lab also did DNA testing on the shotgun and found it a match with Hernandez.

Requiem for a riot

Back at the alley, Sonia Hernandez visited her older brother’s memorial on a recent Saturday that otherwise would have been his 32nd birthday. Since his death, she has spent years protesting police shootings throughout California.

“I felt like he was robbed of justice,” Sonia said. “I do feel some peace knowing that I fought as hard as I could for my brother.”

Toneygay filed a federal lawsuit in 2014, which also represented Hernandez’s son.

Anaheim sought to have the case dismissed, but a judge allowed it to continue and cited an appellate court’s revival of the Cruz suit.

“In a deadly force context, the Court ‘cannot simply accept what may be a self-serving account by the police officer,” the citation read.

But the suit was withdrawn afterward.

Anaheim adopted modest changes since the riots. The city has a police review board and its own Office of Independent Review headed by Michael Gennaco, a former federal prosecutor. OIR completed an audit of Anaheim P.D. in 2019 that included an overview of several shooting incidents dating back years.

“My biggest issue, quite frankly, has to do with the timing of when they interview the involved officers,” Gennaco said of D.A. investigators. “In this case, it should have taken place on March 6 at 10:15 p.m.”

The Hernandez shooting predated those audited, but Gennaco has no general reservations about the supportive role Anaheim P.D. has played in D.A. investigations he reviewed.

“It’s not something that we have seen any evidence of any kind of compromising of the investigation,” he said. “When a shooting happens, there’s a lot that needs to be done. I don’t know if the D.A.’s office has the resources to do it.”

For the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California, which released a 2017 report critical of Anaheim P.D.’s use of force, the cooperation is concerning.

“The Anaheim Police Department had direct involvement in witness interviews and evidence collection, putting into question the independence of the district attorney’s findings,” said Jennifer Rojas, a policy advocate and organizer with the ACLU of Southern California. “When police officers are active participants in the district attorney’s investigation into their own department, it casts further doubt on our criminal legal system’s willingness to hold police officers accountable for deadly shootings.”

Hurtado has since left Anaheim P.D.

What hasn’t changed is how D.A. investigations are carried out, save for Assembly Bill 1506 which now requires that the state attorney general look at cases where an officer shoots an unarmed person.

A spokeswoman for the D.A. defends an approach that largely remains intact between former Dist. Atty. Tony Rackauckas and Todd Spitzer, the current D.A. who unseated him in 2018.

“These investigations are conducted as a collaborative relationship with the involved agency, which is absolutely necessary in order to conduct a fair and thorough investigation,” said Kimberly Edds. “It would be impossible to avoid this crossover due to each investigation being dependent upon the same witnesses, evidence and actors involved.”

Such assurances bring Sonia no comfort. She affixed a small framed photograph of Hernandez to the cross earlier this month. His life and how it ended became part of Anaheim’s history as a prelude to larger protests that year.

“I know he’s remembered in that neighborhood,” she said. “People do care about what happened to him.”

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.