ACLU and activist groups concerned over inmate deaths and COVID-19 procedures in O.C. jails

As four more inmates died last month, civil rights attorneys and local activists are continuing to advocate for better health safeguards in Orange County jails to protect inmates from COVID-19.

They contend that the Sheriff’s Department hasn’t been forthcoming about the true nature of the deaths and continues to forgo basic safety protocols like social distancing and adequate sanitizing.

Jacob Reisberg, a jail advocate for the American Civil Liberties Union, said he’s skeptical of the Sheriff’s Department’s description of the inmate deaths.

“They say at the time of death these individuals were not exhibiting symptoms of COVID-19,” Reisberg said. “They don’t say they didn’t have COVID. They don’t say they didn’t previously exhibit symptoms at a time prior to death. They don’t say they had ever been tested.

“They don’t say whether those individuals may have had other medical conditions, and the strain from COVID on the jail medical system could have exacerbated or led to them to not getting the treatment they need to survive. Looking at just their own words causes a great deal of skepticism.”

Daisy Ramirez, Orange County jails conditions and policy coordinator at the ACLU, said there is a general distrust of Sheriff Don Barnes’ department due to several scandals over the last few years, including the evidence mishandling and illegal confidential informant scandals.

“I think any time that they put out info, the community at large is always skeptical of what is getting out and what’s not getting out,” Ramirez said.

Three of the deceased inmates were at the Intake Release Center facility and another at Theo Lacy jail.

According to the ACLU, the inmates were Charlie Choi, 50; George James, 57; Willie Montes, 63; and James Neal, 73. Each press release from the department on the deaths say the deceased inmate “was not exhibiting symptoms of COVID-19.” The deaths occurred between July 14 and July 22.

Sheriff’s Department spokeswoman Carrie Braun said in an email that no inmates have died from COVID-19. She did not have information on whether the four inmates had been tested for the virus.

Others in the activist community are also skeptical.

Rose Ochoa, founder of Transforming Justice OC, held a car rally last week in front of the central jail complex in Santa Ana to demand an end to inmate deaths in Orange County jails.

“Unfortunately, the Sheriff’s Department withholds a lot of info,” Ochoa said.

The ACLU has been fighting for months to secure better conditions in Orange County jails, setting up a hotline in March for people to reach them while in custody.

The nonprofit launched a class-action lawsuit against the Sheriff’s Department in late April calling for the release of medically-vulnerable inmates and better social distancing, healthcare, testing and personal protective equipment. The Sheriff’s Department has released 800 “low-level” inmates since then. As of Thursday, 512 inmates have tested positive for the virus.

In late May, U.S. District Judge Jesus G. Bernal sided with the ACLU, ordering the department to implement a number of safety protocols in the jails, including social distancing among inmates, regular testing and supplying inmates with adequate cleaning supplies. The Sheriff’s Department appealed the order to the U.S. Supreme Court, which put Bernal’s order on hold last week with a 5-4 decision, effectively releasing the department from implementing the safety protocols.

However, the ACLU is still pursuing the federal case as well as a state case against the department. They are continuing with discovery and talks with the county.

The only response by the Supreme Court was penned by Justice Sonia Sotomayor, who dissented.

“This court normally does not reward bad behavior, and certainly not with extraordinary equitable relief,” Sotomayor wrote in the dissent with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. “Despite knowing the severe threat posed by COVID–19 and contrary to its own apparent policies, the jail exposed its inmates to significant risks from a highly contagious and potentially deadly disease.”

Reisberg remarked: “We share Justice Sotomayor’s disappointment and think that what Judge Bernal had done in his order was extremely reasonable and necessary to protect people inside Orange County jails from the transmission of COVID-19.”

Braun said there have been 11 deaths in Orange County jails so far this year. There were 10 deaths in 2018 and eight deaths in 2019 in county jails, according to the Sheriff’s Department. According to data from the California Department of Justice, 77 people died in county jails between Jan. 1, 2010 and Jan. 1, 2020.

“I am pleased with the Supreme Court’s decision to stay the order,” Barnes said in an emailed statement. “As this litigation is ongoing, I will not comment on the lawsuit. This case will be tried in court, and not in the media. As always, we will protect the constitutional rights of the inmates in our care.”

In its appeal to the Supreme Court, the county contended that the Sheriff’s Department had implemented “robust COVID-19 protocols” prior to the ACLU’s litigation. The county also argued that the injunction limited the ability of local officials to make quick decisions “without fear of running afoul of a federal court injunction.”

“The injunction seizes all aspects of jail administration as to COVID-19 mitigation measures and prevents critical and rapid responses to the virus in an ever-changing landscape,” the court documents say.

Braun said two key highlights of the department’s COVID-19 protocols are enhanced medical screening for all inmates, law enforcement and staff entering the jail, including a temperature screening, and all incoming new booking inmates are quarantined for at least 14 days and tested prior to their release into general housing.

Concerns over the state of Orange County jails and inmate deaths is nothing new. Two Orange County Grand Jury reports over the last few years found deficiencies with jail conditions.

A 2017-2018 report found that 44% of deaths in the jails from 2014 to 2017 could have been prevented by timely and adequate medical care. A 2018-2019 report found that 15 people who died in custody showed evidence of prior cardiovascular history.

Reisberg said they’ve had reports through the inmate hotline that inmates in “barracks-style” housing, like at Theo Lacy, are not socially distanced.

“They can still reach out and touch the person lying in the next bunk or underneath them,” he said.

Ochoa said in addition to the lax COVID-19 prevention protocols, the jails are treating inmates inhumanely.

She said while inmates are banned from seeing family and friends, staff and guards are seeing their families and friends and are not forced to be regularly tested for the virus.

“Staff and guards go home or out to wherever they are going to go and come back the next day bringing whatever it is they may have contracted from outside, inside,” Ochoa said. “Meanwhile, people on the inside are on lockdown, isolated from family and friends. That has been really hard for them.”

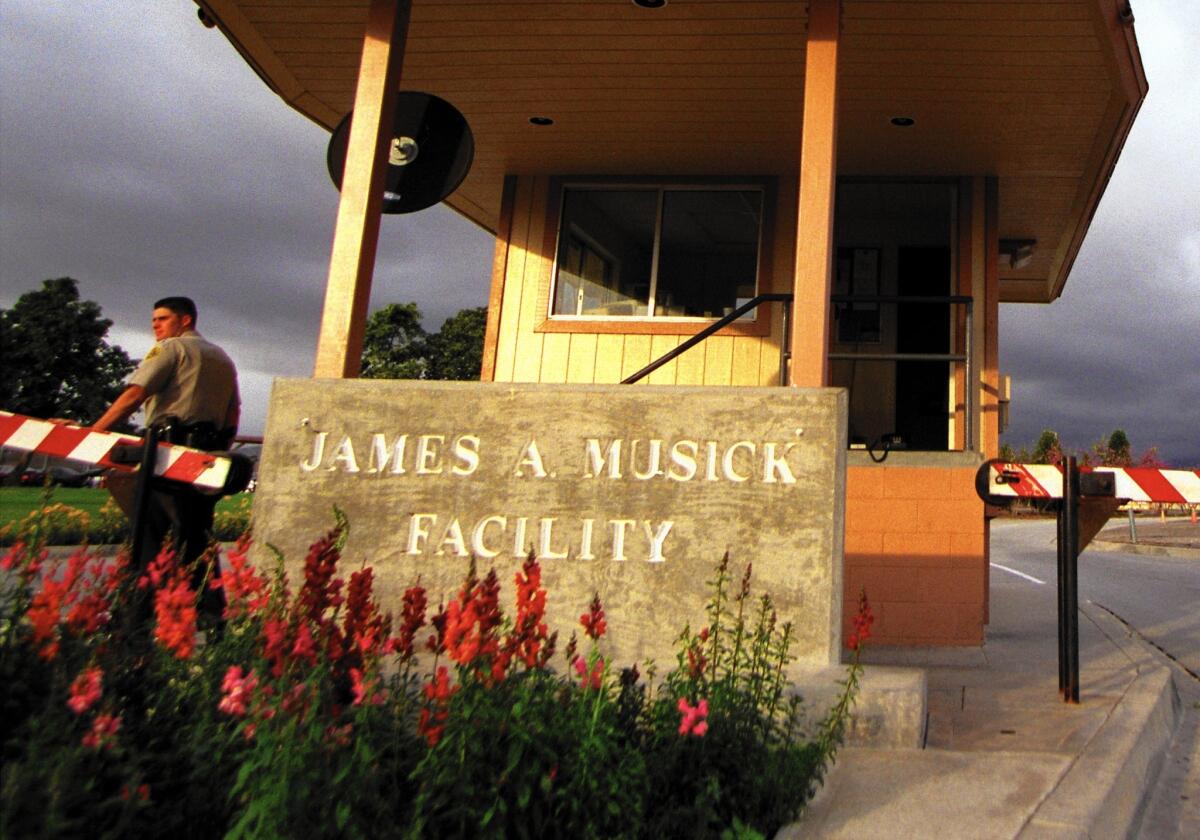

The ACLU is also concerned with the department’s planned $289-million expansion, not including operating costs, of the James A. Musick jail in Irvine — a move they consider unnecessary and financially irresponsible amid a pandemic economy.

Reisberg said the expansion is happening “at a time when the population is at an all-time low, and at a time when we need to be thinking about how to address people’s needs in the community and not putting them in places where they are subject to COVID-19 and the other harms from incarceration.”

Braun said the jails currently house about 3,400 inmates, with a total capacity of 7,483. However, due to closures at the Musick jail and construction projects at the Intake Release Center and Theo Lacy facilities, there are currently 5,570 total beds that are usable.

“The Musick Project is a critical component of our ongoing efforts to reform our custody operations, move forward the integrated services plan, and ultimately help inmates achieve mental health stability and sobriety while in our care and custody,” Barnes said in a statement. “[Thirty-three percent] of our jail beds are more than 50 years old, and 70% of our jail beds are more than 30 years old. These new facilities will better meet the needs of today’s inmate population.”

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.