He was one of the first black cops in O.C. His memoir reveals struggles with racism and why he was forced out

Harlen “Lamb” Lambert sat attentively a year ago as Daniel Michael Lynem, a former Black Panther, spoke about his life during a small gathering at the Heritage Museum of Orange County in Santa Ana.

The last time the two met, Lambert arrived in uniform at Lynem’s family home on June 5, 1969.

“Sir, you are under arrest as a suspect for the murder of a police officer,” he informed Lynem, before reading the Panther his Miranda rights.

Lambert was the first black cop in Santa Ana and one of the first in the county. The night before, Lambert’s fellow Santa Ana officer Nelson Sasscer had been slain while on patrol.

The Orange County district attorney dropped the case against Lynem a month later, but successfully prosecuted Arthur League, another Panther from the Santa Ana branch of the party, for second degree murder.

The Panthers put a hit on Lambert, one serious enough for him to move his family from Santa Ana to Tustin.

“When that hit was ordered, it just didn’t sit well with two or three of us,” said Mustafa Khan, a Panther at the time. “We worked out a situation where another guy told Lambert to get his family out of there.”

As Lynem took questions from the Heritage Museum audience, Lamb, now based in Fullerton, rose up.

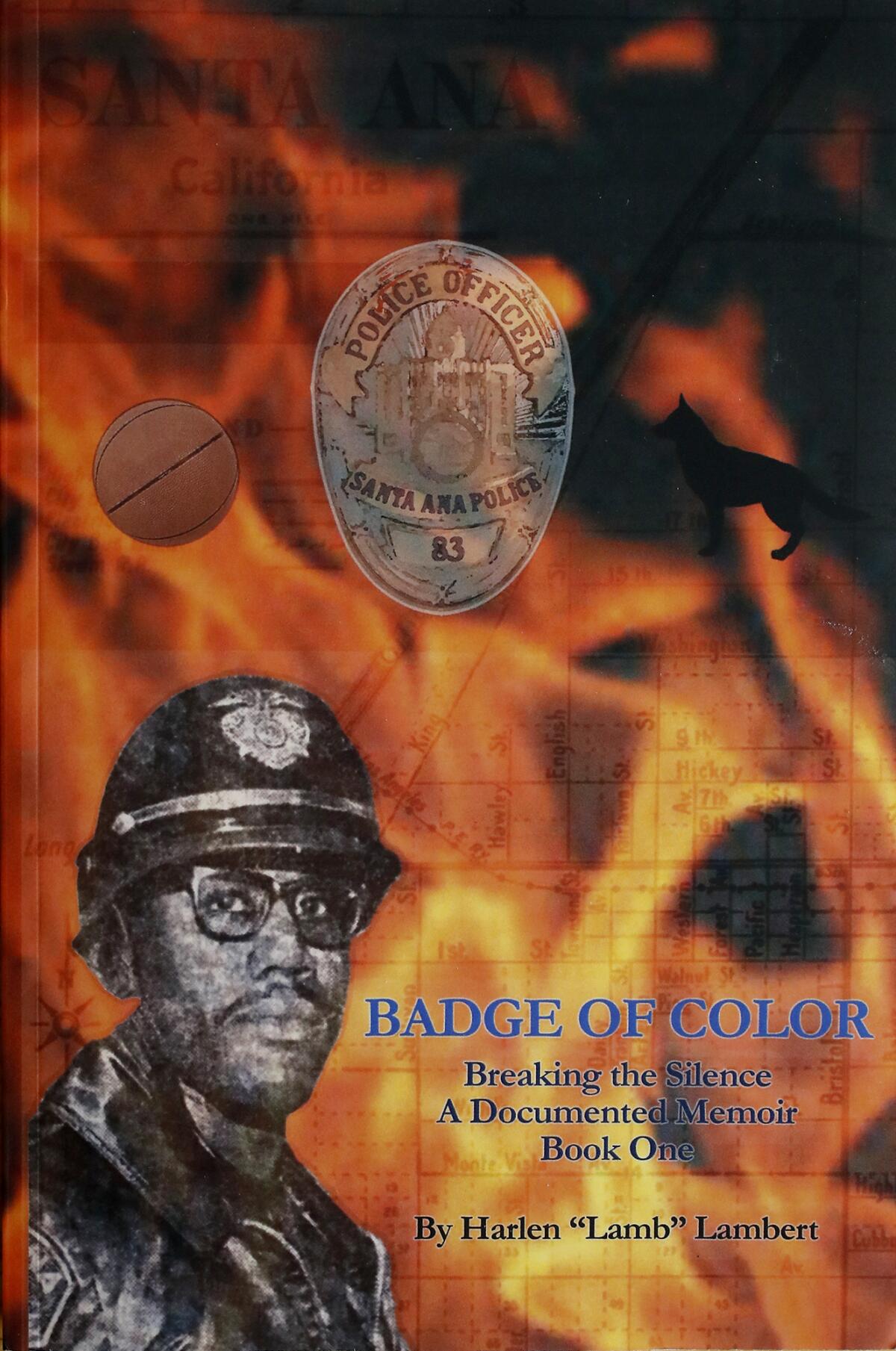

He announced “Badge of Color: Breaking the Silence,” a memoir about the racism he faced while an officer with the Santa Ana Police Department during the 1960s, was finally forthcoming after much promise.

“You were right,” Lambert told Lynem. A hush fell over the crowd.

After the event, Lambert approached the former Panther turned pastor and embraced him.

Fifty years later, Lambert and Lynem didn’t renounce the past that both have moved on from. The former policeman’s words weren’t so much an endorsement of the Panther ideology Lynem no longer subscribes to, but an acknowledgment of a common experience of racism.

“It was definitely a very special moment,” said Kevin Cabrera, executive director of the Heritage Museum of Orange County. “They were both trying to do good for the community. It was good for both of them in being able to reconcile with the past.”

With “Badge of Color” published in September, the encounter played out like a fitting epilogue to a story long-suppressed by the now 83-year-old author.

“I never wished anybody bad luck,” Lambert said, reflecting back. “But I’m glad that I was able to do what I did and leave.”

***

In the 1960s, a small community of African Americans came to define southwest Santa Ana as “Little Texas” with many having left the Lone Star State for O.C.

Born in Louisiana, Lambert grew up in Pine Bluff, Ark., during Jim Crow segregation. He came to Santa Ana by way of Chicago, to ready himself for a professional basketball career almost within reach.

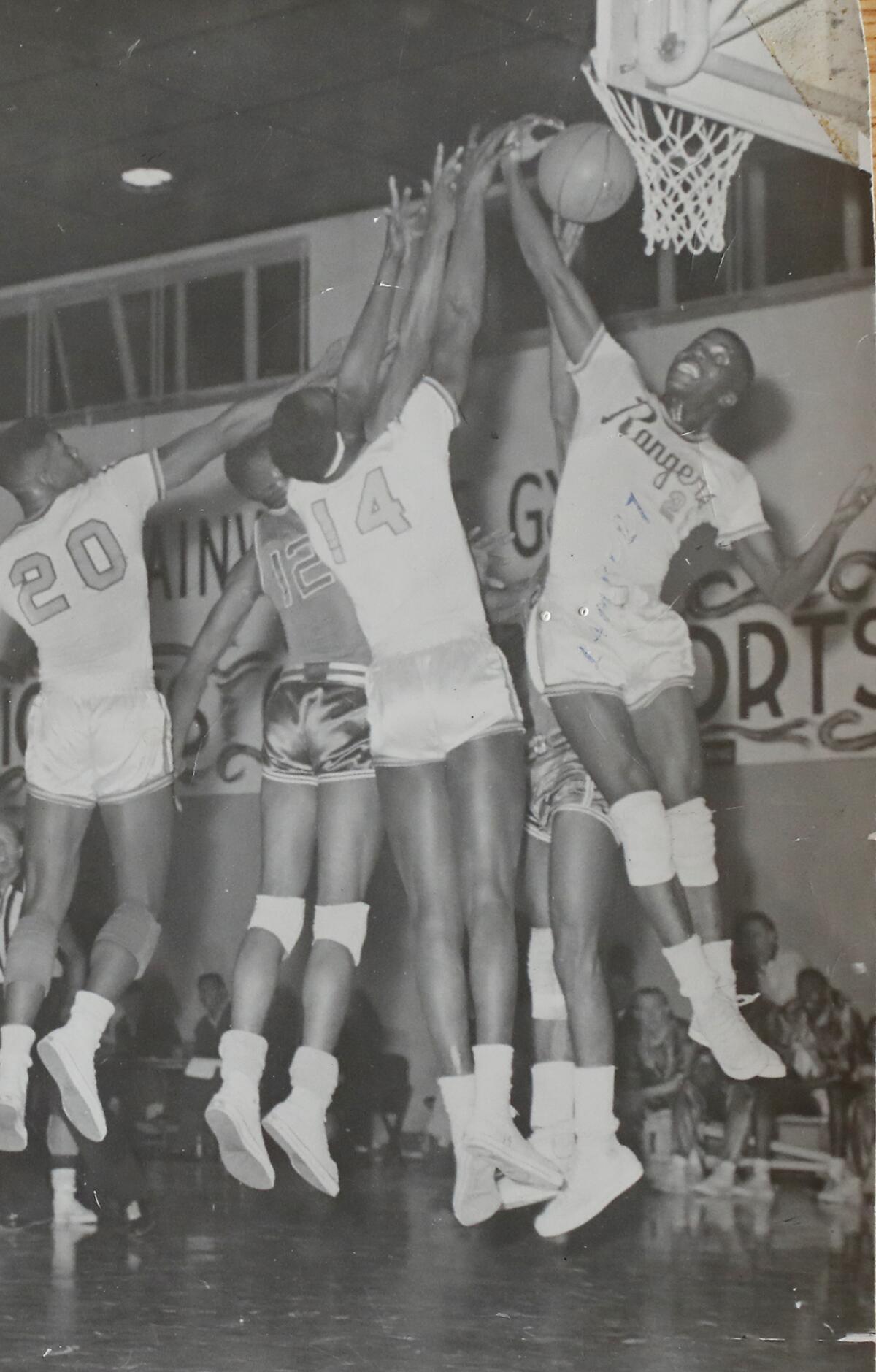

While serving in the military, Lambert earned a spot on the All Army Basketball team. With pride, he took a moment to flip through a folder, stopping at a photo showing him midair grabbing a rebound.

“Look at that one right there,” he said, pointing to the picture with a chuckle.

Lambert played with the team in Europe before deciding on which of several athletic scholarships to accept, including one from the University of Southern California. Unfortunately, he had to sit out a season on account of a rule change. The basketball coach at USC suggested he keep his skills sharp playing for Santa Ana College. By the time a year passed, the coach ended up leaving USC, and Lambert lost his scholarship. His life as a Trojan never came to be.

Settling into Santa Ana while raising a young family, Lambert took a part-time job as a motorcycle escort for funeral processions. A Santa Ana policeman watched him in action a few times before approaching him with the suggestion of joining the force. Lambert hadn’t really thought about being a cop aside from one conversation with black officers serving with the Los Angeles Police Department after a pick-up game of basketball a few years prior.

Santa Ana’s small but active black community vocally pushed for inclusion in the ranks. By 1965, the OC Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) demanded a police oversight board and the hiring of black officers on the city’s force to improve relations. O.C.’s NAACP chapter echoed the latter call as well.

Police Chief Edward J. Allen told the press his department had done outreach in southwest Santa Ana, albeit with a caveat.

“We aren’t about to lower our standards just to permit Negroes to join the police force,” he told the Santa Ana Register at the time.

Lambert wrote in his journal at the time that he felt he could be a bridge between the department and the city’s black and Latino residents. Without much fanfare, Lambert passed his background check and physicals.

In January 1967, he officially became the first black law enforcement officer in Santa Ana’s history in a department roiled in strife between then-Chief Allen and dozens of far-right John Birch Society loyalists determined to oust him.

Nothing about Lambert’s historical task at hand came easy. The prologue to “Badge of Color” painfully recalls Officer Verlyn Powers, whose real name was changed in the book, driving to a dark street and ordering Lambert out of his patrol car. Powers, a field training supervisor originally from Mississippi, sped off, later reappeared, called Lambert the n-word, and told him to get back in the car — but not before accelerating each time he touched the door handle.

Despite the racial hazing of those early days on the force, Lambert anchored himself in the belief that if he modeled professionalism, things could change.

“I was naïve, for awhile,” Lambert admitted. “When things got really bad, I said to myself, ‘I have a job to do.’”

“Badge of Color” details the tribulations Lambert endured from some of his fellow officers and residents. Once his time with Powers ended, he hoped that his harassment, too, would cease.

But by then an article about Lambert’s hire had appeared in the Santa Ana Register and published his home address, giving tormentors — whoever they were — an easy target.

On one occasion, someone stuck a knife on the front door of his house, pinning a KKK business card to it. Others routinely called with threatening messages, including one calling him a “[n-word] pig” following a promise to rape his then-wife.

Vandals flooded the home with a water hose and dumped garbage out on his front lawn. No one was ever held accountable for such actions.

Early on-duty encounters with the black and Latino community didn’t endear him to either. After playing basketball at a park one day, Lambert noticed a group of black men approaching him. They called him an “Uncle Tom” and threatened to pummel him. He reached for his pistol, issued a warning and felt relief when the move scared them off.

The force later assigned Lambert to its newly formed Community Relations department. His main task was to deescalate the increasing tensions between the Panthers and police. The gulf between them became impossible to bridge after the night of Sasscer’s slaying on June 4, 1969.

“I got off at 11 o’clock that night,” Lambert recalls. “I had already put on my civilian clothes when the department called me.”

The next day, Santa Ana PD sent him and Tom Parrott, the only other black cop at the time, to arrest Lynem.

The murder ignited tensions against police as black and Latino youth broke out in small-scale riots. Civil rights groups decried a heavy-handed response in their community. Chief Allen tried to calm things down during a town hall where outraged residents complained about officers using racially-derogatory terms.

But inside the department, Lambert says Allen served as his most powerful ally against the Birchers determined to drive both of them out. He recalls the chief as having been “a good man.”

As the Sasscer murder case unfolded, Lambert watched two Panther brothers under protective custody who served as key witnesses for the prosecution. That’s when he learned of the party’s hit against him.

“That really took a toll on me,” he said.

The department took the threat seriously enough to take Lambert off the case as requested.

“He had no one to turn to,” says Khan, who played basketball with Lambert as a youth. “He couldn’t rely on the police department. He couldn’t go to many black people. When I was in the party, the only person I would have any compassion for was Lamb. He was just isolated.”

***

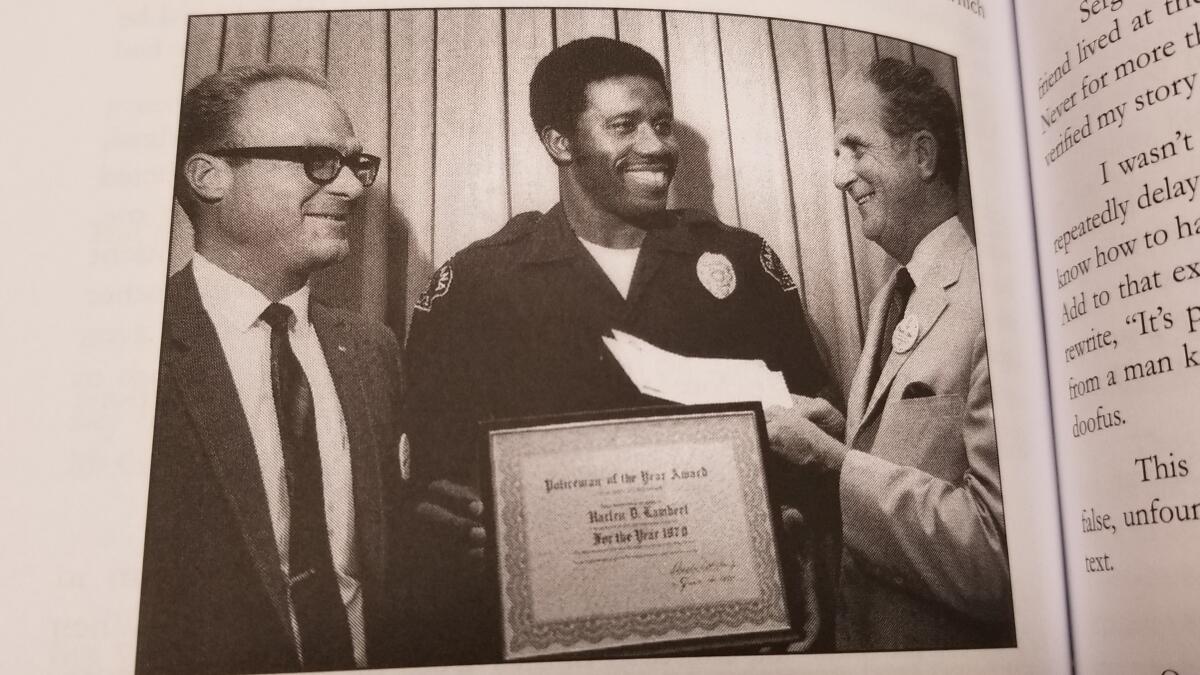

In addition to the historical distinction Lambert earned by being Santa Ana’s first black policeman, by 1970, he gained another more official honor from the Santa Ana Police Department: Officer of the Year.

The early morning of May 26, 1970, started off as a normal graveyard shift for Lambert until he came upon a house engulfed in flames. He radioed for the fire department to arrive. In the meantime, a neighbor shouted that children remained inside the home.

“I ran to the back of the house, which was falling in,” Lambert recalls with tearful emotion.

“God, what do I do?” he thought to himself.

“I went through the window and brought a little girl back through it,” he says. “By that time, nobody helped me except for one officer. I looked up and another little kid was crying.”

Lambert returned into the inferno and reemerged having pulled another child away from the flames.

The fire department arrived on scene and rescued a third child trapped inside. The cause of the house fire was later attributed to a mother who had fallen asleep on a couch with a lit cigarette.

She didn’t survive. Thanks to Lambert and the second cop arriving on scene, all three children inside the home did.

After accepting Officer of the Year for this act of heroism, he returned to his locker alone to discover a sketch of a noose.

Lambert spoke with an Orange County Evening News reporter about the house fire and what his experience as a black officer with the Santa Ana Police Department had been like. A resulting June 7, 1970, headline proclaimed “Tough to be a Hero When You’re a ‘[N-word] Cop.’”

“I sensed that it was the beginning of the end, that my life as a cop would soon change forever,” Lambert writes in “Badge of Color.”

By then, his wife, who had moved back to Chicago with their son after the Panther death threat, wanted a divorce. Inside the department, he witnessed police planting drugs on people before arresting them and using excessive force.

“I’ve seen some officers do some bad things,” said Lambert, “but I couldn’t go rat because their sergeant was my sergeant and I don’t know what buddy systems were at work.”

Lambert says that while none of that behavior became subject to probes, he faced continued harassment, including in the form of unwarranted accusations of alleged misconduct.

Continued complaints about Lamb’s conduct on the job led to eventual suspensions. By 1972, the Register published a feature on his views of O.C.’s race relations from behind the badge. It was one of the last articles on him while still on the force. In the piece, Lambert mentioned he began writing a book about his experiences as a history-making lawman.

The original working title came to him after the article published: “[N-word] Pig.”

“I had no problem saying it as I knew it and lived it every day,” Lambert wrote.

Chief Allen retired later that year. By then, Sgt. Brandon Webb, whose real name was also changed in Lambert’s memoir, had long picked up where Powers left off.

During a routine traffic stop, a white driver accused Lambert of racial retaliation and refused to sign his citation. But since Lambert didn’t call in a field sergeant to clear the arrest, Webb capitalized on the moment, writing Lambert up to the new chief who, in turn, suspended him.

One final investigation by the sergeant, who had been nicknamed “The Vulture,” finally led Lambert to leave law enforcement behind for good in May 1973.

“I’m not going to say Webb’s real name, but he was the reason I quit,” Lambert said. “I’d been asked many times, ‘Why did you quit?’ I told people as much as I wanted them to know.”

***

Even though Lambert secured a copyright for his original working title in 1972 and typed up 156 pages of memories to be fine-tuned into a manuscript, he buried the pain of his time as a policeman immediately after leaving the force.

He kept himself preoccupied with a business training security dogs that became successful during his suspension from the police department.

Lambert eventually remarried in 1984, but largely kept his time as a cop away from his wife for years before tying the knot. Sharron Read-Lambert eventually helped him reconnect with his personal history — and the unfinished task of completing his memoir.

“He had some first drafts,” she says. “When I learned that he was not recognized even as a human being in Orange County, it just really made me angry. I was going to make this happen.”

Read-Lambert dusted off the manuscript one day in 2005, after the couple retired. She read through her husband’s copious notes from his time as a policeman and interviewed him extensively.

The memoir began taking shape as the couple headed off to Santa Ana Library’s History Room for research. Lambert was inexplicably missing from a photo book of Santa Ana police officers put together in 1979 by two members of the force.

In 2008, Lambert tried renewing a concealed carry permit when he stumbled on some hidden history. Then a lieutenant, former Santa Ana Police chief Carlos Rojas informed him that his personnel files remained despite it being department protocol to purge them after five years. Lambert discovered how the internal file jacket framed his time on the force. None of the accolades made it in; he says he found a trove of “half-truths” about incidents he’d never heard of before, instead.

Lambert assumes the unflattering portrait played a role in his never being hired as a policeman ever again despite having interviewed with nearly two dozen departments over the years. The revelation fueled his fire to break his silence and finally complete the memoir.

Self-published in September, Lambert is happy to finally tell his story. His efforts to build a bridge with a badge didn’t prove to be all in vain.

“He knocked down a lot of barriers or limitations that we had toward police,” Khan said. “Personally, he was the first police officer that I had ever looked at as a person.”

The memoir is also a contribution to the vision his mother instilled in him during Jim Crow segregation, one recounted in the book. Speaking of racial harmony, she told Lambert, “One day, son, all the flowers will be in one field, I promise.”

When asked what that means to him now, Lambert grins and points to his wife of 36 years, a white woman.

He chuckles but admits that such a society is still out of reach. A few months ago, the married couple left the parking lot of a bank in O.C. when a young man screamed “Go home, [n-word]!” at Lambert from a passing car.

Racism may be more emboldened these days, but so is Lambert when talking about what he endured as Santa Ana’s first black cop.

“I was erased into obliteration,” he writes in “Badge of Color’s” afterword. “I refuse to be silent any longer.”

For more information, visit new.lamblambertauthor.com.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.