Spate of gang violence in Burbank renews past concerns

Magdalena Araujo was knitting footies for her grandchild in the living room of her Elmwood Avenue home when a bullet flew through her window and pierced the side of her torso.

It was Feb. 22, 1992.

The bullet came out of a .22 caliber rifle fired from a cul-de-sac down the street, the notorious stomping ground for the Barrio Elmwood Rifa gang.

There, members had what police at the time called a “tactical advantage,” as they were uniquely positioned to see oncoming cars. They’d wait for rivals to show up, grab their weapons and open fire.

Join the conversation on Facebook >>

That’s what happened that day. A man looking for the freeway made a wrong turn onto the street.

Many mornings, police — typically in groups, because there’s safety in numbers — would find garage doors covered in 7-foot block graffiti letters, shot-out street lights and urine-filled bottles that were thrown at patrol cars.

Fearful residents slept in their bathtubs to avoid stray bullets.

“It just kept snowballing, snowballing, snowballing, until it couldn’t be denied anymore,” said Ed Skvarna, a gang detective at the time who’s now chief of police at Bob Hope Airport.

Araujo survived. The bullet lodged against her spine, leaving her partially paralyzed, according to news accounts at the time.

But the attack — and others like it — vigorously shook the community, moving people from all corners of Burbank to coordinate a response that included a major law-enforcement crackdown, as well as the development of programs targeting at-risk youth.

It didn’t stop there.

The nonprofit Burbank Housing Corp. was established to buy, fix up and rent properties on Elmwood Avenue.

Workers planted thorny rose bushes and bougainvillea to prevent gang members from hiding weapons in the plants and installed a hard-to-scale fence blocking their escape route.

A gang unit established three months after the shooting was instrumental that year in obtaining a court order banning 88 gang members — with monikers like “Trigger Happy,” “Bam Bam” and “Creeper” — from gathering on the 100 block of West Elmwood Avenue.

The first name listed in court papers? Araujo’s attacker.

Burbank police officials say they’ll never allow the community to return to that level of violence.

But as police investigate five gang shootings, two in one day, and three gang stabbings in recent months with a skeleton staff and no dedicated gang-enforcement detail, some who remember Burbank’s history fear the agency lacks resources to target gang crime in a proactive way.

“Before, when there was an actual gang unit, these police officers knew all these gang members,” said Raha Arnold, asset manager of the Burbank Housing Corp., noting the recent uptick in activity. “I could send them a picture of graffiti, a moniker of one of the people, and they would know, on the spot...It’s unfortunate that they aren’t able to be on top of it the way they were.”

Gangs are homegrown

According to police, Burbank has four gangs with a collective membership of roughly 40, though the number fluctuates as members move, are imprisoned or return home from jail.

Elmwood and the Westside Playboys are the most active, while Burbank Trece Rifa and Raza Brown Pride are smaller.

They still feel that this is their area. This is their hood, this is their property, this is where they want to be. So they come and wreak havoc.

Raha Arnold, asset manager of the Burbank Housing Corp.

The recent violent crime started Nov. 29, about a year and a half after the police gang detail was disbanded.

That afternoon, police believe a gunman in a black Toyota Prius fired on a group of men in Verdugo Park. No one was injured.

Four hours later, a bullet flew through a resident’s window — he was home at the time — on the 200 block of West Verdugo Avenue. Police found bullet holes in multiple garage doors in the area.

A month after that, on the afternoon of Dec. 31, two men in a black sedan drove by that same block, yelling gang-related obscenities before opening fire on two people, striking and injuring one, an 18-year-old man.

“There was a time when you had a gang unit you had people who were contacting the players involved in all these things on a regular basis that would say, ‘I know that car and I know who drives it,’” said police Lt. JJ Puglisi. “If we were more engaged, would we have known?”

All three cases are unsolved.

“They still feel that this is their area,” Arnold said, noting that she recently evicted a family after a teenage boy violated house rules and brought a BB gun inside. “This is their hood, this is their property, this is where they want to be. So they come and wreak havoc.”

Other recent cases were swiftly resolved.

Five suspects in a Dec. 16 gang fight in which a bat and a knife were used in and around Robert Lundigan Park — Playboy turf — were caught and charged within a week.

A shooting at the same park a couple months later left a 21-year-old man wounded.

In that case, detectives recognized the description of the getaway car and tracked down the suspected gunman — as well as a woman believed to have instigated the retaliatory attack — the following day.

“These past few incidents, we’ve been lucky that we still have some folks that were engaged and involved with the people that were involved,” Puglisi said. “I don’t know that that’s always going to be the case.”

There’s no easy definition of gang crime

When addressing the public, police officials are inconsistent in defining gang crime. While the widely accepted definition is any crime that involves a gang member, whether as a suspect or a victim, police often focus on criminal motivation.

At a recent Police Commission meeting, Burbank Police Capt. Denis Cremins indicated that there was only one serious gang-related crime this year, referring to the Feb. 4 Lundigan Park shooting.

See more stories from the crime and public safety desk >>

He wasn’t counting a car-to-car shooting a few nights later, or a stabbing the week before, both of which involved gang members, but apparently weren’t motivated by gang affiliations. Both cases were solved within 24 hours.

Most of Burbank’s gangs formed in the mid-1980s, evolving from pickup football games. Members were mostly Hispanic, but joining had more to do with territory than race or ethnicity, observers said.

“From their point of view, they were soldiers of the neighborhood,” Skvarna said. “It was incumbent upon them to protect their neighborhood from outsiders.”

Most still function this way, save for Burbank Trece, which in recent years has turned into more of an association gang, due to recruitment in jails and prisons, though some inmates have never even stepped foot in Burbank. Now, most of its members, as well as its leader, are described by police as Armenian.

Investigators also keep tabs on Glendale’s Westside Locos, as well as North Hollywood’s Clanton 14 Street and Neighborhood Felons, as their activity can spill into Burbank.

In their early years, the Burbank gangs were larger, as were the number of crimes. Around the time Araujo was shot, Burbank police logged at least 10 gang-related incidents a month. That July alone, it was 30.

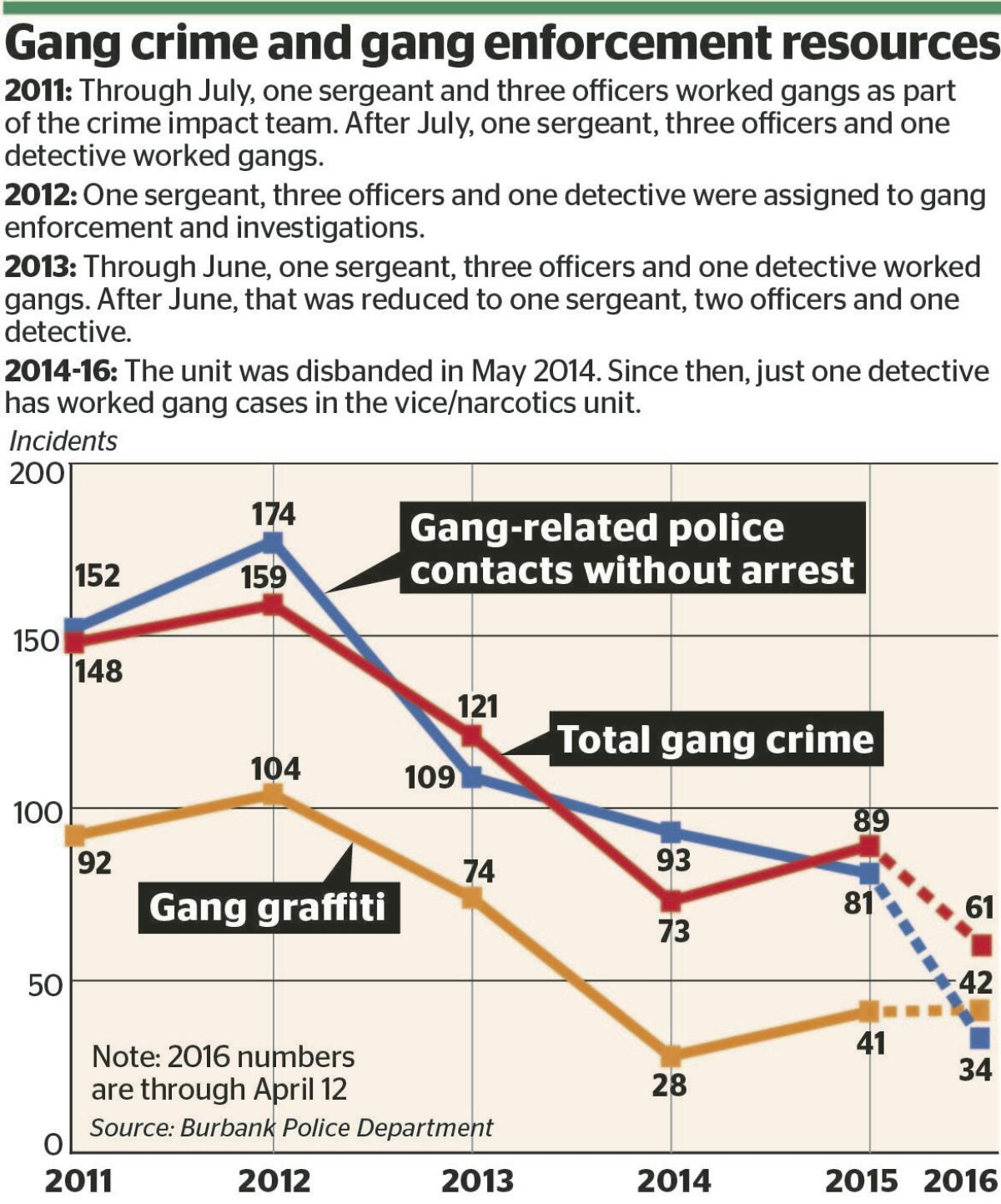

Since that time, the agency consistently staffed a gang sergeant and gang detective, though the number of officers would fluctuate, depending on staffing, according Puglisi.

The folding of the gang unit

That’s until May 2014, when staffing needs changed and the unit folded, leaving one detective in the vice/narcotics unit assigned to investigate gang crime.

A dedicated gang detail brings immeasurable investigative and preventive value, police sources said.

(Steve Greenberg)

Gang officers have the time and training to develop strong ties to the street by building rapport with gang members and gathering intelligence without being bogged down by regular calls for service.

Gang crime reached its lowest point in recent years in 2014, the same year the unit disbanded, with 73 gang-related crimes, down from 148 in 2011, according to statistics released by Capt. Armen Dermenjian.

The statistics include violent and property crimes, as well as gang graffiti.

Though other factors come into play, without a gang detail gang crime increased to 89 incidents last year, while the number of non-arrest contacts officers had with gang members in Burbank plunged from 152 in 2011 to 81.

These contacts are tracked by “field interview cards.”

When officers talk to a gang member when no crime was committed, they’ll log the interaction on an index card, documenting names, addresses and phone numbers, the circumstances of the stop, who the member was with, what they were driving, as well as descriptions of tattoos and scars.

During a gang enforcement patrol April 8, the night after a gang stabbing in a Jack in the Box parking lot involving Elmwood and Playboys, Det. Henry Garay and Lt. Adam Cornils logged a handful of cards.

During one contact, they reminded a 30-year-old Playboys member involved in the Dec. 16 gang fight to register with the court as a gang member.

“So he can’t go to court and say, ‘Nobody told me,’” Garay said.

Shortly after, the duo stopped an older Elmwood parolee released from prison in January of last year after he was convicted in 2002 of attempting to kill a Westside Locos member the year prior.

He’d failed to signal for a turn — a minor vehicle code violation but “enough to have a chat,” Cornils said.

While Cornils searched the car, a flurry of texts popped up on a passenger’s phone. Cornils recognized the name of another Elmwood gangster.

“A lot of times when we’re out, they’ll start texting each other, ‘Hey, gangs is out,’” Garay said.

After clearing the call, he and Cornils drove into a gas station in Elmwood’s turf, where a Westside Locos parolee, Russell “Mosca” Torres, was in handcuffs after patrol officers spotted him with a bag of chili cheese Fritos and found out he had a warrant for his arrest.

“They’re up to no good,” Garay said, suspecting he’d been with other gang members. “They’re in Elmwood territory, tatted head-to-toe with Locos.”

Ball caps reflect affiliations

Nearby, a few minutes later, they spotted another Westside Locos member wearing a Green Bay Packers hat. He was standing alone next to a telephone pole in a residential section of Elmwood territory.

The “G” on his hat stood for Glendale, the cops explained, adding that Toonerville favors Texas Rangers gear while Burbank gangs lean toward the Boston Red Sox or the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Cornils stopped the car. He and Garay hopped out for a brief exchange.

“I’m a Green Bay fan,” the gangster said, lamenting quarterback Aaron Rodgers’ supposed retirement.

“He’s not retiring,” Garay said. It was just before midnight, Garay’s 17th hour at work that day. “Where’s Green Bay at?”

“Minnesota,” the gangster said.

The officers chuckled, to his chagrin, and he then caught himself.

“No, no, Wisconsin,” he said.

After searching him, Garay told him to leave the area.

“Mosca’s in jail, don’t wait here for him. He’s with us,” Garay said. “Inform everybody he’s in custody again.”

They cleared the call: “gang F.I.,” or “gang field interview.”

Police sources say these are crucial to build intelligence, as gang members no longer readily admit their affiliations because of tougher gang sentencing laws.

And while police management says every officer in patrol should be making these contacts, others in the agency say those officers are too busy rushing between calls.

“Is it true that every officer can work gangs and gang crimes?” said an agency veteran, who requested anonymity. “Yes. Is every officer going to be effective in doing that? Motivated in doing that? No. We have officers that specialize in certain areas for a purpose.”

For prevention, consistency and being proactive is key, the source said.

“If you have an active gang unit, you can be actively engaged in reducing the likelihood that shooting is going to take place ... Maybe you recover the gun before the shooting ever happens,” the source said. “I don’t know if you can put a value on that.”

While Burbank Police Chief Scott LaChasse said he moved the gang investigator into vice/narcotics to make the unit a “force-multiplier,” some in the agency said that unit is now stretched too thin.

Currently, the gang detective, with help from the others in vice/narcotics, balances conducting his investigations with court duties, all the while having to maintain a presence on the street, especially when feuds are active.

While it’s nearly impossible to predict when and where a shooting will take place, investigators do find clues on the street.

Gang grafitti on the streets of Burbank.

Gang grafitti on the streets of Burbank. (File photo)

`The newspaper of the street’

Early one January morning, police discovered a gang member’s moniker written in marker on an apartment complex on the 2300 block of North Frederic Street.

Next to it, “187,” the penal code section for murder, appeared, clearly a threat.

The night after the Jack in the Box stabbing, Garay and Cornils came across “PBS,” short for Playboys, spray-painted on an apartment building on Elmwood’s turf.

Right away, Garay asked the city’s graffiti-removal contractor to clean it up before a rival gang member had a chance to show up and cross it out, a sign of disrespect.

“We don’t want to start a cross-out war,” Garay said. “If we can remove graffiti as fast as possible, it’s beneficial.”

One of the first homicides Skvarna investigated, in 1985, stemmed from a similar act of disrespect.

A Cypress Park gangster crossed out Burbank Trece graffiti and replaced it with his gang’s insignia. He was shot and beaten to death by rivals armed with steel weapons and spikes.

Investigators read the writing on the walls as a reflection of any ongoing conflict. Gang members may be marking their turf, intimidating rival gang members, making blatant threats or commemorating past crimes.

Without a strong police presence, feuds can easily erupt into violence, sources said.

“Graffiti is the newspaper of the street,” Skvarna said. “If graffiti is really prevalent, that’s a pretty good metric that the gang problem has increased.”

After two years of significant decreases, reaching its lowest point — at 28 incidents — in 2014, Burbank saw an uptick in gang graffiti last year to 41 reported incidents. Already this year, there have been at least 42 incidents.

A vast majority of the city’s total graffiti, gang-related or not gets reported straight to the city contractor in charge of cleaning it up. In recent years, total graffiti removal numbers — which include spray paint, chalk and sticker graffiti — have plummeted, from 11,499 incidents in 2011 to 5,565 last year, according to the city.

Removers photograph and log each image into a database available to the gang detective.

“We were getting flooded with stuff, intelligence,” Skvarna said of his time as a gang investigator. “Stuff we didn’t know about.”

Without a dedicated gang unit, the agency is less aggressive in following these leads, police sources said.

While management countered that it’s difficult to identify vandals when they fail to leave a moniker, some rank-and-file members said that’s where the gang unit would prove invaluable.

“If you had gang officers contacting these people, they’d find paint, markers, cans and writing on books or in phones,” said another member of the force, who asked not to be named.

Some say there is no room for a full-time detail, given staffing shortages. The agency is struggling to fill 12 vacancies while waiting for seven recruits to graduate from the academy.

Burbank residents and parents have asked the city to consider restoring the full gang enforcement unit, as well as the five school resource officer positions cut during the recession.

Others have taken it upon themselves to be more vigilant. Since November, Burbank police have registered 12 new Neighborhood Watch groups.

At least one of those, police said, was in direct response to a gang-related stabbing.

Update on 1992 shooting

Little is known to police about what later happened to Araujo, the grandmother who was shot in 1992. Officers no longer keep in touch. Her listed neighbors had no information.

Public records indicate she is now in her early 70s. Multiple efforts by the Burbank Leader to reach her proved unsuccessful.

But newspaper accounts from the time of the shooting described her as an innocent victim of gang violence.

--

Alene Tchekmedyian, [email protected]

Twitter: @atchek