Last Monday, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a new report that followed August’s initial portion of this massive, three-part effort. Much of the immediate news coverage has focused on the latest attempts to communicate the seriousness of the impacts of climate change. The report concludes, “The cumulative scientific evidence is unequivocal: Climate change is a threat to human well-being and planetary health. Any further delay in concerted anticipatory global action on adaptation and mitigation will miss a brief and rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all.”

There is a great deal in this report on our understanding of climate change impacts, which are worsening as warming progresses. These topics should be familiar unless you’ve just stepped out of a time machine (and are not arriving from the future, or they'd be even more familiar). They include everything from sea level rise and weather extremes to food security and direct human health risks.

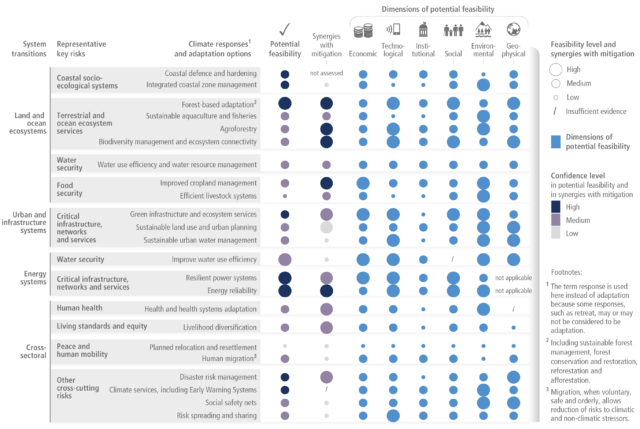

But the other focus of this portion of the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report is adaptation to climate change. It’s easy to throw this term around as if it’s an alternative to halting global warming or some painless thing that will happen of its own accord. Both ideas would be mistaken.

Adaptation by rational selection

At the simplest level, the IPCC report describes the concept like this: “Adaptation, in response to current climate change, is reducing climate risks and vulnerability mostly via adjustment of existing systems.” In mathematical terms, if risk is the result of a physical hazard plus your exposure to that hazard and your vulnerability when exposed, adaptation is a way to bring the total risk back down a bit.

Adaptation is necessary regardless of how aggressively we mitigate warming by eliminating greenhouse gas emissions because the risk never goes down to zero. And as long as we’re trending toward a future that differs from the past, our planning decisions also have to be based on future conditions. Otherwise, we’ll be continually surrounded by the failings of systems that weren’t designed for the world they find themselves in.

Adaptations of the built environment are typically the focus of this conversation, but the report talks about physical, natural, and social infrastructure—a huge variety of systems that affect our exposure and vulnerability to climate impacts.

These systems include ideas as simple as improving early warning systems for weather hazards. With more people increasingly at risk from storm flooding or heat waves, warnings become even more important, as do insurance programs and social safety nets, which can make people much more resilient to financial losses from storm damage. Economic or cultural inequality is a direct impediment to reducing vulnerability, as it ensures a portion of the population shoulders disproportionate risk—living in the lowest (and so, cheapest) parts of an easily flooded city, for example, or lacking access to health care. So anything that addresses these problems is, in addition to however else you would categorize it, climate adaptation.

Agricultural adaptations provide good examples of changes in practice. Farmers learn how to alter planting timing and irrigation as conditions change and can switch to new cultivars or different crops. The fishing industry can also change where and how much it harvests as populations migrate or shrink.

This overlaps with natural infrastructure, the many kinds of value provided to human populations by the ecosystems and environments they inhabit. Restoring or preserving forests, mangroves, wetlands, and the like may not be a new effort, but it can serve the goal of reducing climate risk. Coastal habitats provide storm protection, and forestry around pastureland—and trees in cities—can reduce summer temperatures. Good forestry practices can reduce the risk of wildfire.

And just as improving the resilience of human populations helps in the face of climate impacts, supporting ecosystem health similarly strengthens them.

Adaptations in the built environment include modifications to all kinds of traditional “infrastructure”—roads, rails, electric grids, and storm drains—as well as urban planning. The report notes that many of the adaptation measures we’ve seen implemented so far relate to water, whether that’s flood control or water supply. Sea level rise is an obvious example, as the area threatened is pretty well-defined. Responses can range from sea walls all the way to the relocation of existing communities.

reader comments

75